Although this guide is very detailed, the information contained is not exhaustive and is intended only to provide general guidance and information about the right to refuse unsafe work.

How to use this guide:

- Purpose of this Guide

- The Statutory Right to Refuse

- Statutory Limits

- Steps to Promote Workplace Safety

- The Decision to Refuse Unsafe Work

- Steps to Follow in Refusing Work

- Protection Against Employer Reprisals

- The Regulatory College

- Exception to the Obey and Grieve Rule

- Appendix 1 – Can I Refuse? Scenarios

- Appendix 2 – Health-Care Residential Facilities

- Appendix 3 - CNO Practice Guideline

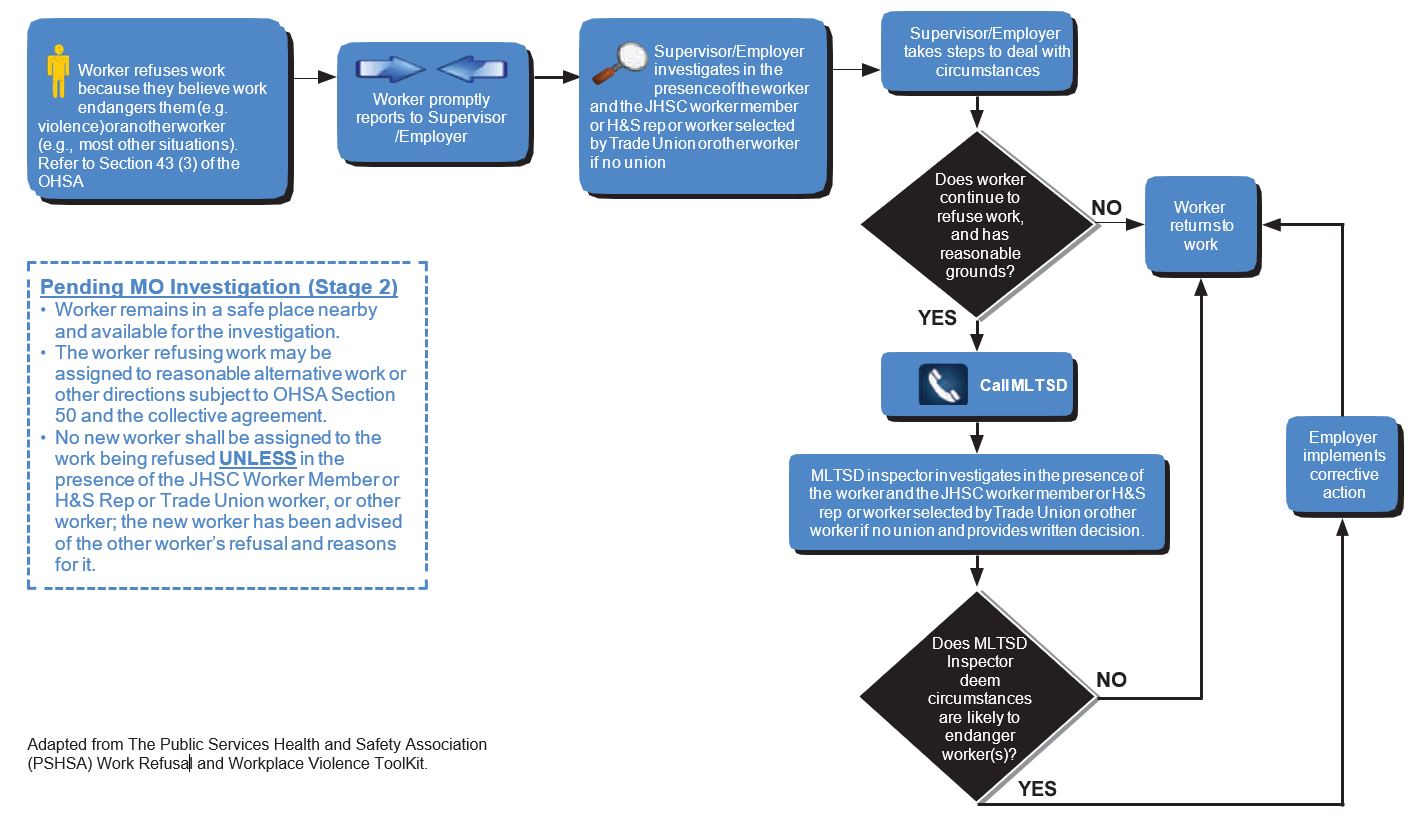

- Appendix 4 – Work Refusal Flowchart

Purpose of this Guide

Workers in Ontario have three fundamental rights under the Occupational Health and Safety Act (OHSA). These rights are:

- The right to know

- The right to participate

- The right to refuse unsafe work.

This guide helps to explain the right to refuse unsafe work.

A health-care practitioner’s (HCP) conduct is subject to review and possible sanctions in assessing whether and to what degree one’s conduct is aligned with ethical codes. Ethics are a set of rules or standards developed within a health-care profession that guides the actions of individuals while working in their professional capacity. There are four main ethical principles that guide the development of a practitioner’s standards. Ethical principles such as Non-malfeasance (i.e., “above all do no harm”) and Beneficence (i.e., actions should promote good) are two of the principles at play in this context and serve as a basis for HCP’s ethical values and principles. They are not a private concern to the HCP or the profession, but developed in dialogue with society, and are open to public scrutiny. [1] For the purpose of this guide, we will review examples of these key ideas in the most relevant standards and practice guidelines from the College of Nurses of Ontario (CNO) in the section entitled, “The Regulatory College and Unsafe Working Conditions” (Page 9).

The employer is responsible for providing a safe practice setting where every precaution reasonable in the circumstances is taken to protect workers. This includes providing the appropriate equipment, staffing and training for safe and effective infection control, safe patient/resident/client handling, protection against violence, etc.[2] The employer should make all workers aware of and current on such things as hazard information, material safety data sheets, employer policies and provincial directives regarding infectious diseases.

While health-care workers are protected under Ontario’s OHSA, many of them are among those workers who, under that legislation, have limitations on their right to refuse unsafe work. There is another right to refuse apart from the statutory right which can be found in the section entitled, “Exception to the Obey and Grieve Rule” (Page 12).

1. Canadian Nurses Association (2017). Code of Ethics for Registered Nurses. Retrieved from; https://www.cna-aiic.ca/~/media/cna/page-content/pdf-en/code-of-ethics-2017-edition-secure-interactive and Keatings, M. & Smith, O. (2010). Ethical & Legal Issues in Canadian Nursing (3rd ed.). Toronto, ON: Elsevier Canada.

2. Whenever patient is identified, this may refer to patient/client/resident.

The Statutory Right to Refuse

In Ontario, the OHSA establishes the right to refuse unsafe work without fear of reprisal. According to Section 43 of the Act, the circumstances in which a worker can refuse include circumstances where the worker has reason to believe that:

- Any equipment, machine, device or thing the worker is to use or operate is likely to endanger the worker or another worker;

- The physical condition of the workplace or the part thereof in which the worker works or is to work is likely to endanger the worker; or

- The physical condition of the workplace is in contravention of this Act or the regulations and such contravention is likely to endanger the worker or another worker;

- Workplace violence is likely to endanger the worker; or

- Any equipment, machine, device or thing the worker is to use or operate or the physical condition of the workplace or the part thereof in which the worker works or is to work is in contravention of this Act or the regulations and such contravention is likely to endanger the worker or another worker.

Section 43 also sets out the procedures to be followed when a worker refuses unsafe work. Section 50 sets out the complementary right of a worker not to be fired, disciplined and/or threatened for exercising this right.

Statutory Limits on ONA Members’ Right to Refuse

As stated, ONA members’ right to refuse unsafe work has limitations under the OHSA. Health-care workers in hospitals and long-term care facilities have a limited right to refuse unsafe work while those who work in the community care sector do not have the same limitations under the OHSA. The workers subject to the restriction include those working in:

- a hospital, sanatorium, nursing home, home for the aged, psychiatric institution, mental health centre or rehabilitation facility,

- a residential group home or other facility for persons with behavioural or emotional problems or a physical, mental or developmental disability,

- an ambulance service or a first-aid clinic or station,

- a laboratory operated by the Crown or licensed under the Laboratory and Specimen Collection Centre Licensing Act, or

- a laundry, food service, power plant or technical service or facility used in conjunction with an institution, facility or service described in subclause (i) to (iv).

These employees still have a right to refuse, but not:

- when a circumstance…is inherent in the worker’s work or is a normal condition of the worker’s employment; or

- when the worker’s refusal to work would directly endanger the life, health or safety of another person.

[Section 43 (1), OHSA]

Here is one example the Ministry of Labour, Training and Skills Development (MLTSD) (formally known as the Ministry of Labour or MOL) uses to explain the exemption:

- An experienced medical lab technologist could not, in the course of regular work, refuse to handle a blood sample from a patient with an infectious disease.

- But the technologist could refuse to test for a highly infectious virus where proper protective clothing and safety equipment are not available.

Dealing with infection is likely “inherent in the worker’s work” in a health-care facility, but doing so without proper protective equipment, where such exists, is not “inherent.”

There is now at least one ONA work refusal that supports this approach. During Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), an ONA member exercised their right to refuse unsafe work when the employer requested that they care for a SARS patient without being fitted with the required N95 respirator. The MLTSD upheld their work refusal and ordered that this worker not be required to care for a SARS patient until they were properly fit-tested with an N95 respirator. The MLTSD ordered the employer to further comply with Section 10 of the Ontario Regulation 67/93 – Health-Care and Residential Facilities (fit-testing section) and to develop a plan to immediately fit-test all workers.

Examples:

- Infectious diseases: most ONA members have a right to refuse to work where unsafe conditions exist and they are not adequately protected through infection control procedures and equipment. Individual circumstances, such as lack of adequate respiratory protection will need to be addressed at the institutional level and the member will need to make a judgment call, weighing the risks against the client’s need for care.

- Patient handling: The same principle applies to other hazards such as patient handling. Patient handling is likely “inherent in the worker’s work” in a health-care facility, but transferring patients without adequate equipment where such exists or without adequate staffing is not “inherent.” Again, members will need to make a judgment call based on individual circumstances, such as lack of proper lifting equipment and/or staffing, weighing the risks against the client’s need for care.

ONA believes that a member who has to refuse work because adequate protection was not made available would therefore avoid the exemption under the Act and have the benefit of the right to refuse.

For some of our members, the OHSA does not impose restrictions on their legal right to refuse unsafe work. Under the OHSA, our members who do not work in the facilities specified above, such as public health, Local Health Integration Networks, industry and clinics have the same right to refuse unsafe work as the broader workforce. Of course, all of our regulated professionals’ rights are circumscribed by their obligations to their professional colleges, such as the College of Nurses of Ontario (CNO).

Steps to Promote Workplace Safety

The right to refuse work is an important one, but it should not be the first line of defense against unsafe conditions. Identifying hazards and finding solutions to implement the hierarchy of controls (i.e., elimination/substitution) is the best line of defense to protect a worker and to prevent exposures/injury/illnesses in the workplace. Being proactive before the hazard places a member in immediate danger will help to avoid work refusal situations.

Therefore, when the danger is not immediate, a worker should first report health and safety concerns to their supervisor, JHSC, and if necessary, to the MLTSD. Workers are expected to take these steps, if possible before considering a work refusal.

JHSCs should be working now to verify that appropriate safe work conditions, infection control measures, violence policies, safe patient handling programs, safe staffing levels and all measures, as outlined in Section 8 and 9 of the Ontario Regulation 67/93 – Health Care and Residential Facilities (attached at Appendix 2), are taken to protect worker health and safety. These can include developing respiratory protection programs, safe lift programs (which include purchasing an adequate supply of mechanical devices/ceilings lifts etc.), infectious disease prevention programs (which include replacing old needle and sharp devices with safety engineered devices, pandemic planning), violence prevention programs, etc. If the JHSC is unsuccessful in its efforts to resolve the worker’s concerns, the worker or a member of the committee should call the MLTSD.

The Decision to Refuse Unsafe Work

Subject to the restrictions outlined above, an ONA member can refuse to work if they have reason to believe that:

- Workplace violence is likely to endanger the worker.

- The physical condition of the workplace or the part thereof in which the worker works or is to work is likely to endanger the worker.

OR the worker has reason to believe that the worker or another worker is likely to be endangered by:

- Any equipment, machine, device or thing the worker is to use or operate.

OR the worker has reason to believe that:

- Any equipment, machine, device or thing the worker is to use or operate, or the physical condition of the workplace or the part thereof in which the worker works or is to work is in contravention of the OHSA/Regulations and such contravention is likely to endanger the worker or another worker.

Steps to Follow in Refusing Work

Note: Refer to the Work Refusal Flow Chart (Appendix 4).

First Stage:

- The worker must immediately tell the supervisor or employer that the work is being refused and explain why. The member should document all of the details pertaining to their work refusal.

- The supervisor or employer must investigate the situation immediately, in the presence of the worker and a JHSC member who represents workers, or another worker chosen by the union.

- The refusing worker must remain in a safe place that is as near as reasonably possible to the workstation and available to the employer or supervisor for the purposes of the investigation until the investigation is completed. (No other worker shall be assigned to do the work that has been refused unless, in the presence of a JHSC worker member who, if possible, is a certified member, or another worker chosen by the union has been advised of the other worker’s refusal and of their reasons for the refusal.) If the situation is resolved at this point, the refusing worker returns to work.

- Following the investigation, the worker can continue to refuse the work if they have reasonable grounds for still believing that the work continues to be unsafe.

Second Stage:

- The worker, union or employer must cause an MLTSD inspector to be notified (“cause” notification suggests that the task of notifying may be delegated to a representative of the worker, union or employer). The inspector should come to the workplace to investigate the refusal and consult with the worker and the employer (or a representative of the employer). The worker representative from the first stage will also be consulted as part of the inspector’s investigation.

- While waiting for the inspector’s investigation to be completed, the worker must remain during the worker’s normal working hours in a safe place that is as near as reasonably possible to the workstation, and available to the inspector for the purposes of the investigation, unless, subject to the provisions of a collective agreement, the employer assigns some other reasonable work during normal working hours. If no such work is practicable, the employer can give other directions to the worker.

- The inspector must decide whether the work is likely to endanger the worker or another person. The inspector’s decision must be given, in writing, to the worker, the employer and the worker representative identified above, if there is one. If the inspector finds that the work is not likely to endanger anyone, the refusing worker will normally return to work. (See below for what happens if the worker does not).

- Although the Act does not cover this point, the Ontario Labour Relations Board (OLRB) has ruled that a refusing worker is considered to be at work during the first stage of a work refusal and is entitled to be paid at their appropriate rate under the Act. The Act does state that a person acting as a worker representative during a work refusal is paid at either the regular or the premium rate, whichever is applicable.

Protection Against Employer Reprisals

- The employer is not allowed to penalize, dismiss, discipline, suspend or threaten to do any of these things to, or impose any penalty on or intimidate or coerce, a worker who has used this process in good faith. Note that to exercise an initial right to refuse, the worker does not need to be correct; they only need to have “reason to believe” that unsafe circumstances exist.

- A worker may continue their work refusal after the Ministry inspector decides it is safe, but they are taking a great risk. If disciplined at this stage, they will need to convince a tribunal that they are correct and the inspector is wrong in order to avoid the consequences (e.g., discipline for insubordination).

- If you are disciplined or threatened after exercising your rights described above, consult your Bargaining Unit leadership/Labour Relations Officer for advice and assistance.

- If a member has been disciplined contrary to the OHSA, there is a choice to be made by the union: the matter can be decided either by arbitration under a collective agreement, or by a complaint to the Ontario Labour Relations Board. In either case, the burden of proof is on the employer.

The Regulatory College and Unsafe Working Conditions

Nurses and other regulated health-care workers have to consider their standards of practice established by their regulatory College. Each College has different statutory considerations when looking at the refusal of unsafe work. These will be addressed in several scenarios outlined in Appendix 1.

For example, the CNO has two key standards and one practice guideline that are relevant in this context, namely the Professional Standards (2002), Ethics (2018), and Refusing Assignments and Discontinuing Services (2017). Refusing Assignments and Discontinuing Services (attached at Appendix 3) was developed by the CNO in response to SARS. The CNO’s position at the conclusion of SARS was that, while nurses are committed to meeting the needs of clients, the provision of professional nursing services does not include working in situations where nurses’ health is at risk and no precautions have been taken. These documents describe ethical values that are most important to the nursing profession in Ontario, and describe professional expectations for all nurses in every area of practice, along with some examples of these key ideas:

- Seeking assistance appropriately and in a timely manner.

- Taking action in situations in which patient/resident/client safety and well-being are compromised.

- Maintaining competence and refraining from performing activities for which they are not competent.

- Providing; facilitating; advocating; and promoting best possible care for patient/resident/client.

- Advocating for a quality practice environment that supports a nurse’s ability to provide safe effective and ethical care.

- Using their knowledge and skill to promote patient/resident/clients’ best interests in an empathic manner.

- Identifying when their own values and beliefs conflict with the ability to keep implicit and explicit promises and taking appropriate actions.

- Making all reasonable efforts to ensure that patient/resident/client safety and well-being are maintained during any job action.[3]

These key ideas are important because in health-care settings, harms are not justifiable, unless they set back the patient’s interests temporarily to provide a longer-term benefit. Professional practice standards and guidelines express the competencies that HCPs must have to ensure the provision of safe and ethical patient care. Some actions of HCPs may produce temporary harm, such as administering medications by injection as a form of sedation or chemical restraint when caring for a client exhibiting violent behaviour, and/or restraining clients who are at risk to themselves or others. This temporary harm is justified if it is a means to producing a good outcome and respects the ethical principle of Autonomy.[4]

The following are underlying principles set out by the College to guide a nurse’s decisions and actions when presented with situations in which they may consider refusing an assignment or discontinuing services:

- The safety and well-being of the client is of primary concern.

- Critical appraisal of the factors in any situation is the foundation of clinical decision-making and professional judgment.

- Nurses are accountable for their own actions and decisions and do not act solely on the direction of others.

- Nurses have the right to refuse assignments that they believe will subject them or their clients to an unacceptable level of risk (College of Nurses of Ontario, 2003).

- Individual nurses and groups of nurses safeguard clients when planning and implementing any job action (Canadian Nurses Association, 2002).

- Persons whose safety requires ongoing or emergency nursing care are entitled to have these needs satisfied throughout any job action (Canadian Nurses Association, 2002).[5]

The following are key expectations set out by the College when selecting the appropriate course of action:

- Carefully identify situations in which a conflict with their own values interferes with the care of clients (College of Nurses of Ontario, 2004b, p. 10) before accepting an assignment or employment.

- Identify concerns that affect their ability to provide safe, effective care.

- Communicate effectively to resolve workplace issues.

- Become familiar with the collective agreement or employment contract relevant to their settings and take this into account when making decisions.

- Learn about other legislation relevant to their practice settings.

- Give enough notice to employers so that client safety is not compromised.

- Provide essential services in the event of a strike.

- Inform the union local and employer in writing their ongoing professional responsibility to provide care, which will continue in the event of any job action.[6]

Nurses have the right to refuse assignments that they believe will subject them or their clients to an unacceptable level of risk (CNO, 2003a, pg. 9). Nurses working in unsafe situations assume a level of risk and may need to determine for themselves if the risk is too high. Personal safety, professional and ethical issues need to be considered, but as with most ethical choices, there is no single answer that clearly resolves the issue. Nurses must consider their rights as well as their responsibilities and use a problem-solving approach.

If you choose to refuse an unsafe assignment, you can still meet professional obligations to the client by informing your employer of why you are refusing, documenting your decision-making process and attempting to provide the employer with enough time to find a suitable replacement. If the reasons for the refusal are resource or support-based, following these steps will demonstrate your commitment to a quality practice setting:

- Assess the situation to determine the problem, the key individuals affected by the problem and the decision needed.

- Gather additional information to clarify the problem.

- Identify the safety, professional and ethical issues.

- Identify who should make the decision (e.g., you alone; you and the Occupational Health and Safety Representative; you and your College).

- Identify the range of actions that are possible and their anticipated outcomes.

- Decide on a course of action and carry it out. This decision-making process can be applied in most unsafe work situations. Using this process also shows a commitment to ongoing reflective practice.

The CNO’s Ethics professional standard prescribes that nurses demonstrate regard for client well-being by “making all reasonable efforts to ensure that client safety and well-being are maintained during any job action.”[7] (e.g., exercising right to refuse in the context of unsafe working conditions). The College could require you to demonstrate that you have taken all available steps to protect yourself before you exercise your right to refuse. Resolving ethical dilemmas resulting from conflicting obligations requires the thoughtful consideration of all relevant factors and sometimes there is not one best solution, but only the best of two imperfect solutions.[8]

If there is a complaint or report to the CNO arising out of your refusal to work, you should contact ONA’s Legal Expense Assistance Plan (LEAP) Team Intake at LEAPintake@ona.org for immediate information and advice. On written notification from the College, you will be provided with an advocate to represent you. Also advise your Bargaining Unit President/Labour Relations Officer. You are advised not to speak to the College before you have contacted LEAP.

3. College of Nurses of Ontario (2018). Ethics Practice Standard. Retrieved from https://www.cno.org/globalassets/docs/prac/41034_ethics.pdf

4. Canadian Nurses Association (2017). Code of Ethics for Registered Nurses. Retrieved from: https://www.cna-aiic.ca/~/media/cna/page-content/pdf-en/code-of-ethics-2017-edition-secure-interactive and Keatings, M. & Smith, O. (2010). Ethical & Legal Issues in Canadian Nursing (3rd ed.). Toronto, ON: Elsevier Canada.

5. College of Nurses of Ontario (2017). Refusing Assignments and Discontinuing Nursing Services. Retrieved from: https://www.cno.org/globalassets/docs/prac/41070_refusing.pdf

6. College of Nurses of Ontario (2017). Refusing Assignments and Discontinuing Nursing Services. Retrieved from: https://www.cno.org/globalassets/docs/prac/41070_refusing.pdf

7. College of Nurses of Ontario (2018). Ethics Practice Standard. Retrieved from: http://www.cno.org/globalassets/docs/prac/41034_ethics.pdf

8. College of Nurses of Ontario (2017). Refusing Assignments and Discontinuing Nursing Services. Retrieved from: https://www.cno.org/globalassets/docs/prac/41070_refusing.pdf

Exception to the Obey and Grieve Rule –The Right to Refuse Beyond the Statutory Provision

Years before there existed a statutory right to refuse unsafe work, arbitrators developed what came to be known as the “obey now and grieve later” rule. These arbitrators said that the workplace is not a debating society: the general rule is that when the employer gives a direct order, it must be obeyed even if the order is contrary to the collective agreement. The issuance of the order and any discipline imposed for failing to comply with it can be challenged through the grievance procedure, but in the meantime the order must be complied.

Arbitrators developed a limited number of exceptions where they may reverse the discipline imposed when an employee refuses an employer’s order. One of those exceptions is when the order involves the performance of work which will injure the worker. If a worker can establish the likelihood of injury, they may succeed in overturning discipline for refusing the order.

Up to the point that an MLTSD inspector is called, the statutory right provides more protection for work refusal than the exception to the arbitral “obey now and grieve later’ rule. As has been pointed out, under the OHSA, an employee only has to have a reasonable belief that the work is dangerous up to that stage.

After an inspector rules that the work is safe, however, an employee must be correct to justify continued refusal, whether they want to rely upon the OHSA or the arbitrator’s rule.

It is possible that the arbitral rule provides more protection at this point. The OHSA expressly cannot be used to protect against employer discipline where the refusal would directly endanger a patient. However, it is possible to argue that an arbitrator should find that the exception to the “obey now and grieve later’ rule continues. Consider, as an example, the outbreak of a new pandemic where protective equipment would delay but not avoid death for the health practitioner. An arbitrator might be more likely to protect the right of such an at-risk worker to refuse to expose themselves through the arbitration rule than through the statute.

These are the type of arguments that ONA representatives can and will make to defend members who have been disciplined for refusing to work under unsafe conditions. Before they actually refuse, however, members must realize that none of these arguments are guaranteed to succeed. Each member must consider their obligations under their college and weigh the risks of refusing against the risks of performing the work.

Questions

If you have any questions regarding this guide and your right to refuse unsafe work, contact your Bargaining Unit President and/or Labour Relations Officer

I have been assigned directly to a Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (i.e., COVID-19) patient and have been provided only with a surgical mask, not the N95 respirator. I have read that the ordinary surgical mask does not provide sufficient protection. I have raised the issue with my supervisor who said I have no choice as they have run out of N95 respirators. I have to work now, and I don’t have time to call a JHSC member. Can I refuse to work?

Answer – The Occupational Health and Safety Act

If you determine after a point of care risk assessment that you require an N95 and your employer does not provide you with one, we believe that in this circumstance the MLTSD should support your work refusal. It would be ONA’s position that while an infectious agent may be expected in a workplace, it is not inherent in your work that you work in an area where an infectious agent is present, without being protected by personal protective equipment. There is continuous emerging evidence of the airborne transmissibility of COVID-19 and of the need for an N95 respirator to protect you from “a highly infectious virus” when dealing with a COVID-19 patient.

Remember that to exercise an initial right to refuse, the worker does not need to be correct, they only need to have “reason to believe” that unsafe circumstances exist.

If the employer/supervisor’s investigation into the work refusal makes a finding that it is safe to return to work without the proper respirator and the refusing worker has reasonable grounds to still believe the work is unsafe, then the MLTSD must be called in to investigate and make a ruling.

A worker may continue their work refusal after the Ministry inspector decides it is safe, but they are taking a great risk. If disciplined at this stage, they will need to convince a tribunal that they are correct and the inspector is wrong in order to avoid the consequences.

Answer – College of Nurses of Ontario

We believe that in this circumstance the College should support your work refusal. Nurses have the right to refuse work where unsafe conditions exist and they cannot be adequately protected through infection control measures i.e., provision of a N95 respirator when providing care to a COVID-19 patient.

According to the CNO, nurses can withhold services if they can:

- Provide an appropriate rationale.

- Notify the employer of the risk/protection concerns when infection control is inadequate.

- Hand over the care responsibilities for assigned clients to the supervisor.

When nurses withhold patient care services, careful decision-making is required. Be sure to document the situation carefully step-by-step, which can include completing a professional responsibility workload report form (PRWRF). In the event the CNO becomes involved, all circumstances pertaining to the situation will be considered on an individual case-by-case basis.

Answer – Collective Agreement Language

Check your collective agreement for helpful language about personal protective equipment such as N95 respirators. Use it in conjunction with the OHSA and the advice from the CNO to take steps to prevent you from ever needing to consider a work refusal. Your Labour Relations Officer can assist bargaining unit leadership in the use of the language and strategies to prevent and address hazardous situations in the workplace.

I am assigned directly to a TB patient and have been given the proper personal protective equipment recommended by the Ministry of Health, Health Canada, the Centre for Disease Control and all official bulletins and have been properly fit-tested for the equipment. With all the news reports, I still do not feel confident that I am protected. Can I refuse to work?

Answer – The Occupational Health and Safety Act

There is really no “reason to believe” that unsafe circumstances exist since the proper personal protective equipment has been provided.

We also think the MLTSD would NOT support a work refusal in this instance, as they may find exposure to a disease, for which you have proper protective equipment, is inherent in the work and that removing yourself from the work may directly endanger the patient.

Answer – College of Nurses of Ontario

The College may find that you have abandoned your patient in this scenario. It would be prudent for nurses to be mindful of and to make a clear distinction between unsafe working conditions and inherently risky work, such as caring for patients with infectious diseases while using appropriate safety precautions. The Nursing Act includes regulations that define professional misconduct. Definitions of professional misconduct may be relevant in situations in which nurses refuse assignments or discontinue nursing professional services when they have been provided with proper protective equipment while caring for clients with an infectious illness. Although there is no specific definition of professional misconduct that includes the word abandonment, the definitions can guide nurses on what might constitute professional misconduct related to refusing an assignment or discontinuing nursing services. Each situation would be assessed on its own merit.[9]

Answer – Collective Agreement Language

Check your collective agreement for helpful language about personal protective equipment such as N95 respirators. Use it in conjunction with the OHSA and the advice from the CNO to take steps to prevent you from ever feeling unsafe at work. Your Labour Relations Officer can assist bargaining unit leadership in the use of the language and strategies to prevent and address hazardous situations in the workplace.

I am a radiation technologist and have not been provided with a properly fitted lead apron to use in the operating room or in diagnostic imaging. I know that the health-care regulation under the OHSA requires the provision of protective vests when positioning a patient during irradiation. I have raised the issue with my supervisor who said that I should use what’s available. I have to work now and I don’t have time to call a JHSC member. Can I refuse to work?

Answer – The Occupational Health and Safety Act

We believe that in this circumstance the MLTSD should support your work refusal. It would be ONA’s position that it is not inherent in your work that you work without being protected by known personal protective equipment, particularly equipment that is specifically prescribed by regulation.

In settings where workers are required either by the Health Care Residential Facilities Regulation (O. Reg. 67/93) or their employer to use PPE:

- employers must ensure workers are instructed and trained in the care, use and limitations of PPE before wearing or using it the first time and at regular intervals thereafter

- workers are required to participate in instruction and training

- the PPE provided, worn or used must be properly fitted.

In settings where workers are required either by the Industrial Establishments Regulation (O. Reg. 851) or their employer to use PPE:

- a worker required to wear or use any protective clothing, equipment or device shall be instructed and trained in its care and use before wearing or using the protective clothing, equipment or device.

Remember that to exercise an initial right to refuse, the worker does not need to be correct, they only need to have “reason to believe” that unsafe circumstances exist.

Answer – College of Medical Radiation Technologists

We believe that in this circumstance, the College should support your work refusal and not consider it an act of professional misconduct.

Answer – Collective Agreement Language

Check your collective agreement for helpful language about personal protective equipment such as the proper selection, use and proper fit for radiation protection. Use it in conjunction with the OHSA and the advice from the College of Medical Radiation Technologists to take steps to prevent you from ever needing to consider a work refusal. Your Labour Relations Officer can assist bargaining unit leadership in the use of the language and strategies to prevent and address hazardous situations in the workplace.

I am assigned to work the night shift and we are short staffed. During rounds, I find that a heavy patient has fallen out of bed. I am alone and cannot access other staff to help me lift this patient. I know if I try to lift this patient on my own, I will likely injure myself and then not be able to care for any of the other patients. I call my supervisor and tell them that I believe lifting this patient will injure me and that I cannot do this task without help. They ordered me to try and lift the patient or face discipline.

Answer – The Occupational Health and Safety Act

We believe the MLTSD would uphold your work refusal, providing that you really could not access help and you continue to make your patient as comfortable as possible on the floor and provide care until help arrives. Furthermore, your supervisor may be in violation of section 50 of the Act for threatening to discipline you.

Remember, that to exercise an initial right to refuse, the worker does not need to be correct, they only need to have “reason to believe” that unsafe circumstances exist.

If the employer/supervisor’s investigation into the work refusal (which has to be conducted in the presence of the worker and a JHSC committee member who represents workers, or an OHS representative in workplaces with six-19 workers or a worker selected by the union because of knowledge, training and experience) makes a finding that it is safe to return to work without the proper respirator and the refusing worker has reasonable grounds to still believe the work is unsafe, then the MLTSD must be called in to investigate and make a ruling.

A worker may continue their work refusal after the Ministry inspector decides it is safe, but they are taking a great risk. If disciplined at this stage, they will need to convince a tribunal that they are correct and the inspector is wrong in order to avoid the consequences.

Situations like this should be anticipated and can be avoided by the employer. In this case, we would strongly recommend that you start now to avoid a work refusal by involving your JHSC, and the MLTSD, if necessary. JHSCs can make written recommendations to the employer about proper staffing levels and implementing a safe lift program that includes purchasing proper mechanical device equipment, which may also include a ceiling lift, and ensure that training is part of any program developed.

Answer – The College of Nurses of Ontario

We believe the College would support the nurse because nurses have the right to refuse assignments that they believe will put them or their clients at risk. However, nurses should have a justifiable rationale for their refusal. In this scenario, a two-person lift being attempted by one nurse could put both the nurse and client at risk.

Nurses must inform employers why they are refusing the assignment (e.g., the facility does not have the proper lifting equipment that would ensure the nurse’s safety). The College recommends that the nurse documents all the steps taken prior to refusing the assignment (e.g., telephone call to supervisor and their response, attempts to get help from other units, etc.).

Employers are responsible for creating a work environment, including staffing, that supports safe, effective care.

Answer – Collective Agreement Language

Check your collective agreement for helpful language about workplace health and safety. Use it in conjunction with the OHSA and the advice from the CNO to take steps to prevent you from ever needing to consider a work refusal. Your Labour Relations Officer can assist bargaining unit leadership in the use of the language and strategies to prevent and address hazardous situations in the workplace.

I am a community care nurse. We are not provided with cell phones or other means of communicating. I am to drive to a remote area to provide care to a recovering surgical patient. The home is located five kilometres down a dirt road. I was there last week in good weather. The road is narrow and not well kept and I had some difficulty keeping the car on the road. The weather forecast today calls for freezing rain. I believe it is not safe for me to visit this patient this afternoon. I have expressed my concerns to my supervisor who simply tells me to drive carefully. Can I refuse to work?

Answer – The Occupational Health and Safety Act

We believe the MLTSD would uphold your work refusal. Unlike hospital and homes workers, Ontario Health Home and Community Care Support Services (HCCSS), community, health unit, industry and clinic workers are not identified among those who have a limited right to refuse unsafe work under Section 43(1) (2) of the OHSA. As such, if you have reason to believe that the physical condition of the workplace is likely to endanger you, then you can legally refuse to work. In this case, you have personal knowledge of the physical condition of the road, and in good weather, you experienced difficulty. The weather forecast of freezing rain gives you reason to believe that you will likely be endangered.

Remember that to exercise an initial right to refuse, the worker does not need to be correct, they only need to have “reason to believe” that unsafe circumstances exist.

However, a worker may continue their work refusal after the Ministry inspector decides it is safe, but they are taking a great risk. If disciplined at this stage, they will need to convince a tribunal that they are correct and the inspector is wrong in order to avoid the consequences.

Situations like this should be anticipated and can be avoided by the employer. In this case, we would strongly recommend that you start now to avoid a work refusal by involving your JHSC/H&S Representative and the MLTSD, if necessary, in developing safe driving programs and contingency plans. JHSCs can make written recommendations to the employer about vehicles, intake interviews, alternate safe means of providing care, alternate safe means of transportation, etc.

Answer – College of Nurses of Ontario

Nurses need to demonstrate a problem-solving approach when making decisions about refusing an assignment. The College will only support a refusal if the nurse can demonstrate how they problem solved (e.g., telephone call to local municipality to see if road will be sanded by the afternoon, telephone call to client’s family to see if someone would be with client in the afternoon and if they would be comfortable with the nurse doing a phone visit).

Answer – Collective Agreement Language

Check your collective agreement for helpful language about workplace health and safety. Use it in conjunction with the OHSA and the advice from the CNO to take steps to prevent you from ever needing to consider a work refusal. Your Labour Relations Officer can assist bargaining unit leadership in the use of the language and strategies to prevent and address hazardous situations in the workplace.

I work in a psychiatric unit and my colleagues and I have been subject to abuse in the past in one form or another. I have approached my employer with my concerns, yet nothing further has been done to protect my health and safety. Tonight, I must care for a violent patient by myself as we are short staffed and I have reason to believe that I will be injured. I have requested security to be present on the unit for the shift and the request was denied by the manager. Can I refuse to work?

Answer – The Occupational Health and Safety Act

Our position is that the MLTSD should uphold the work refusal. In 2010 the OHSA was amended to explicitly include workplace violence and harassment and includes the definition of violence and harassment. Violence and threats of violence by a person are real health and safety issues covered by the legislation. A worker has the right to refuse work if a worker believes they are at risk of physical injury from “workplace violence” which is defined as:

(a) The exercise of physical force by a person against a worker, in a workplace, that causes or could cause physical injury to the worker.

(b) An attempt to exercise physical force against a worker, in a workplace, that could cause physical injury to the worker.

(c) A statement or behaviour that it is reasonable for a worker to interpret as a threat to exercise physical force against the worker, in a workplace, that could cause physical injury to the worker.

While it is our position that the MLTSD should uphold the work refusal, the Ministry is reluctant to write orders for additional staffing and therefore may be reluctant to also uphold a work refusal. Case law supports our position that the MLTSD can write orders for additional staffing. In Decision No. 01/93-A (St. Thomas Psychiatric Hospital and Ontario (Ministry of Health) (Re) (unreported, April 29, 1993, AP 01/93A Ont. Adj., D. Randall), the adjudicator supported the inspector’s decision to order safe staffing levels.

If the MLTSD makes a decision not to uphold the work refusal and/or write orders for additional staff or other violence prevention measures, speak to your Bargaining Unit President/Labour Relations Officer immediately to consider appealing the non-issuance of an order by the MLTSD (NB: you only have 30 days to appeal from the date of the Ministry’s decision which is the date the field visit report was issued).

Remember, to exercise an initial right to refuse, the worker does not need to be correct, they only need to have “reason to believe” that unsafe circumstances exist.

If the employer/supervisor’s investigation into the work refusal (which has to be conducted in the presence of the worker and a JHSC committee member who represents workers, or an OHS representative in workplaces with six-19 workers, or a worker selected by the trade union because of knowledge, training and experience) makes a finding that it is safe to return to work without the proper violence prevention measures and the refusing worker has reasonable grounds to still believe the work is unsafe, the MLTSD must then be called in to investigate and make a ruling.

A worker may continue their work refusal after the Ministry inspector decides it is safe, but they are taking a great risk. If disciplined at this stage, they will need to convince a tribunal that they are correct and the inspector is wrong in order to avoid the consequences.

It is strongly recommended that you start reporting hazards to your supervisor now and not wait to be put in a position to exercise a work refusal. Section 28 of the OHSA states as a duty of a worker, a worker shall:

- Work in compliance with the provisions of this Act and the regulations.

- Use or wear the equipment, protective devices or clothing that the worker’s employer requires to be used or worn.

- Report to their employer or supervisor the absence of or defect in any equipment or protective device of which the worker is aware and which may endanger the worker or another worker; and

- Report to their employer or supervisor any contravention of this Act or the regulations or the existence of any hazard of which they know.

Further to reporting hazards, such as workplace violence and the absence of provisions in place to protect worker safety to your supervisor, you should also involve your JHSC to assess compliance with violence prevention requirements of the OHSA, and by calling the MLTSD, if necessary.

The OHSA includes explicit provisions that require an employer to develop a policy with respect to violence, and a program with specific measures and procedures (including on-going risk assessments) to control risk of exposure to, and prevent physical injury from, workplace violence, including domestic violence spillover from home to work. The program must also include a means for summoning immediate assistance when violence occurs or is likely to occur. Talk to your JHSC worker member/H&S representative at your workplace or Bargaining Unit President about what measures and procedures should be in place if in doubt that your employer has an adequate workplace violence prevention program and training to protect the safety of the workers.

JHSCs should assess compliance with these and other provisions of the law and where necessary make written recommendations to the employer to ensure proper staffing levels, appropriate protective measures, and that procedures and equipment and training are in place to protect you and your colleagues.

Answer – College of Nurses of Ontario

We believe solo nursing on a potentially violent psychiatric unit puts both the nurse and other clients at risk, therefore, the College should support the nurse. However, the nurse needs to notify the employer of their concerns, advocate for quality patient care, request additional staffing and document. Give the employer as much notice as is possible so other arrangements can be made for client care.

Additionally, it would be prudent for the nurses to demonstrate if the unit is critically understaffed on an ongoing basis, given the patient population and acuity levels, as well as discuss local practices, and their effectiveness, to address staffing shortages. Documentation in the client(s) charts and client risk assessment tools, e.g. Dynamic Appraisal of Situational Aggression (DASA); along with submission of safety incident reports, occupational health and safety reports, and professional responsibility workload report forms, would serve as strong evidence suggesting to the regulator a “system” issue at the organization with respect to a critical shortage of staff, and would also serve to demonstrate nursing actions to advocate and to ask for help.

Answer – Collective Agreement Language

Check your collective agreement for language about violence prevention. It should be used in conjunction with the OHSA and the advice from the CNO to take steps to prevent you from ever needing to consider a work refusal. Your Labour Relations Officer can assist bargaining unit leadership in the use of the language and strategies to assist hazardous situations such as the management of aggressive patients and others in the workplace.

A number of us work in a small hospital outside the Greater Toronto Area and are concerned that our hospital could be next to receive a COVID-19 patient. We do not feel that the employer is taking every reasonable precaution to ensure our safety. We hear that the public and health-care workers in many Toronto hospitals are being given N95 respirators. Our employer said we don’t need them and won’t provide them. Can we refuse to work?

Answer – The Occupational Health and Safety Act

We think the MLTSD would NOT support a work refusal in this instance because the danger is not immediate. In one case an adjudicator commented:

“The work refusal provisions are not intended to be a substitute for the internal responsibility system with recourse to an inspector through a complaint. “[S]ection 43 is to be used only in urgent circumstances” and not “just because you want a quick answer” to a health and safety concern. (OPSEU and Ontario (Ministry of the Solicitor General and Correctional Services) (Re) (unreported, July 7, 1997, Ont. G.S.B., N. Dissanayake), at page 20.

A work refusal is an individual right. While many workers may legitimately refuse at the same time where each has a sincere belief that they are in danger, a work refusal by a group should not be pre-planned or “staged.”

In this case we would strongly recommend that you start now to avoid a work refusal by involving your JHSC and the MLTSD, if necessary, to verify that appropriate protection measures, procedures and equipment are in place to protect you and your colleagues. The MLTSD has advised inspectors to respond quickly to complaints from workers who have a limited right to refuse unsafe work, for as one adjudicator said, “…workers who engage in inherently dangerous work for the benefit of the public have a right to expect that their employers and the MLTSD will be especially vigilant in ensuring all reasonable precautions consistent with the performance of their duties are taken.” (OPSEU, Local 321 and Ministry of Labour (Re) (unreported, May 4, 1992, AP 09/92, Ont. Adj., R. Blair), at p. 2)

Answer – College of Nurses of Ontario

In the event the College becomes involved, all circumstances will be considered on an individual case-by-case basis. However, in this case, a negative outcome is likely if work was refused before taking all available steps to ensure the safety of yourself or your patients.

Document all steps that you took in order to obtain personal protective equipment before you exercised your right to refuse, as you may need this information to prove to the College that you took every available step to ensure patient safety prior to exercising this right.

Answer – Collective Agreement Language

Check your collective agreement for helpful language about workplace health and safety and personal protective equipment such as N95 respirators. Use it in conjunction with the OHSA and the advice from the CNO to take steps to prevent you from ever needing to consider a work refusal. Your Labour Relations Officer can assist bargaining unit leadership in the use of the language and strategies to prevent and address hazardous situations in the workplace.

I work in a locked unit for dementia patients in long-term care facility and my colleagues and I have been subjected to abuse in the past in one form or another. I have approached my employer with my concerns, yet nothing further has been done to protect my health and safety. One large, male resident has recently had such violent episodes that we have had to restrain him physically and chemically. His medication was reduced today and he the is showing signs of agitation again. Tonight, I must care for him by myself as we are short staffed and I have reason to believe that I will be injured. I have requested one-to-one care be provided to the resident for the shift (there is no security in a long-term care facility and there is funding available for limited one-to-one care from the MOHLTC) and the request was denied by the manager. Can I refuse to work?

Answer – The Occupational Health and Safety Act

Yes, you have the right to refuse unsafe work in this situation. As stated in the previous scenario, the OHSA states that violence and threats of violence by a person are covered by the legislation. The employer is required under the OHSA to develop and maintain a program to implement the workplace violence prevention policy and the program shall,

- include measures and procedures to control the risks identified in the assessment required under subsection 32.0.3 (1) as likely to expose a worker to physical injury.

- include measures and procedures for summoning immediate assistance when workplace violence occurs or is likely to occur.

- include measures and procedures for workers to report incidents of workplace violence to the employer or supervisor.

- set out how the employer will investigate and deal with incidents or complaints of workplace violence.

The employer is also required to assess the risks of workplace violence that may occur in the workplace because of the nature of the workplace, the type of work or the conditions of work. Health care is recognized as having high risks for workplace violence. The violence can stem from direct or indirect patient care, family members, and general public with access to the workplace, and from colleagues.

The employer is required to advise the JHSC or a health and safety representative of the results of the assessment and provide a copy if the assessment is in writing. Ask your JHSC worker member/H&S representative for the results. You have the right to know!

Further to the employer’s duties for protecting a worker from workplace violence, is the employer’s duty to provide a means of summoning immediate assistance when violence occurs or is likely to occur. Working with a client/resident that poses a risk of violence requires measures and procedures in place to protect the health and safety of the worker(s). The MLTSD is reluctant to issue an order for a security guard; however, the “take every precaution reasonable in the circumstance” order under section 25 (2) (h) of the OHSA would in our opinion allow them to issue to this order.

If after refusing the unsafe working condition the MLTSD inspector is called in to make a decision and it does not agree with your reason to believe it’s likely to endanger, it is encouraged that you contact your Bargaining Unit President/Labour Relations Officer at ONA to escalate your concerns with a Director at the MLTSD immediately.

Remember, JHSCs should assess compliance with these and other provisions of the law and where necessary make written recommendations long before being put in a position of imminent risk to the employer.

Answer – College of Nurses of Ontario

This scenario is similar to Scenario 7 wherein the College said:

We believe solo nursing on a potentially violent psychiatric unit puts both the nurse and other clients at risk, therefore, the College is unlikely to find the nurse has committed an act of misconduct by refusing unsafe work in these circumstances. But the nurse needs to notify the employer of her concerns, advocate for quality patient care, request additional staffing and document. Give the employer as much notice as is possible so other arrangements can be made for client care.

Additionally, it would be prudent to advocate for best practices and document care strategies, such as:

- Plan of care and behavioural response strategy for patients exhibiting aggressive behaviour or those who are at risk to themselves or others;

- Plan of care identifying triggers or previous history of aggressive acts and mitigation strategies;

- Engagement with organizations external to health care and health care organizations with a focus on behavioural issues (e.g., behavioural support groups);

- Standardized care pathways and medical order sets for specific conditions; and trained sitters or security guards for risk of physical aggression. [10]

Answer – Collective Agreement Language from the Participating Nursing Homes Template excerpts from Article 6

6.06 (h)

This language has been negotiated over the last two rounds of collective bargaining. It should be used in conjunction with the OHSA and the advice from the CNO. Your Labour Relations Officer can assist the Bargaining Unit President in the use of the language and strategies to assist with the management of aggressive residents up to and including that the home transfer a resident to a more appropriate care setting in accordance with the Long-Term Care Homes Act.

6.06 (h) The parties further agree that suitable subjects for discussion at the Union-Management Committee and Joint Health and Safety Committee will include aggressive residents.

The Employer will review with the Joint Health and Safety Committee written policies to address the management of violent behaviour. Such policies will include but not be limited to:

- Designing safe procedures for employees.

- Providing training appropriate to these policies.

- Reporting all incidents of workplace violence.

(i) The Employer shall:

- Inform employees of any situation relating to their work which may endanger their health and safety, as soon as it learns of the said situation,

- Inform employees regarding the risks relating to their work and provide training and supervision so that employees have the skills and knowledge necessary to safely perform the work assigned to them,When faced with occupational health and safety decisions, the Home will not await full scientific or absolute certainty before taking reasonable action(s) including but not limited to, providing reasonably accessible personal protective equipment (PPE) that reduces risk and protects employees.

- Employees will be fit tested on hire and then on a bi-annual basis or at any other time as required by the Employer, the government of Ontario or any other public health authority.

- The Home will maintain a pandemic plan, inclusive of an organizational risk assessment, that will be shared annually with the JHSC.

- Ensure that the applicable measures and procedures prescribed in the Occupational Health and Safety Act are carried out in the workplace.

(j) A worker shall,

- Work in compliance with the provisions of the Occupational Health and Safety Act and the regulations;

- Use or wear the equipment, protective devices or clothing that the worker’s employer requires to be used or worn;

- Report to their Employer or supervisor the absence of or defect in any equipment or protective device of which the worker is aware and which may endanger themselves or another worker, and

- Report to their Employer or supervisor any contravention of the Occupational Health and Safety Act or the regulations or the existence of any hazard of which they know.

(m) The Joint Health and Safety Committee will discuss and may recommend appropriate measures to promote health and safety in workplaces, including, but not limited to:

- Musculoskeletal Injury Prevention,

- Needle Stick Injury Prevention,

- Personal Protective Equipment,

- Training designed to ensure competency under the Act for those persons with supervisory responsibilities,

- Employees who regularly work alone or who are isolated in the workplace.

6.07 Violence in the Workplace

- The parties agree that violence shall be defined as any incident in which an employee is abused, threatened or assaulted while performing their work. The parties agree it includes the application of force, threats with or without weapons and severe verbal abuse. The parties agree that such incidents will not be condoned. Any employee who believes they have been subjected to such incident shall report this to a supervisor who will make every reasonable effort to rectify the situation. For purposes of sub- article (a) only, employees as referred to herein shall mean all employees of the Employer notwithstanding Article 2.12.

- The Employer agrees to develop formalized policies and procedures in consultation with the Joint Health and Safety Committee to deal with workplace violence. The policy will address the prevention of violence and the management of violent situations and support to employees who have faced workplace violence. These policies and procedures shall be communicated to all employees. The local parties will consider appropriate measures and procedures in consultation with the Joint Health and Safety Committee to address violence in the workplace, which may include, among other measures and procedures:

- Alert employees about a person with a known history of aggressive and responsive behaviours and their known triggers by means of:

- electronic and/or other appropriate flagging systems

- direct verbal communication/alerts (i.e., shift reports)

- Communicate and provide appropriate training and education; and,

- Reporting all incidents of workplace violence.

- Long-term care home wide violence risk assessments.

- Alert employees about a person with a known history of aggressive and responsive behaviours and their known triggers by means of:

- The Employer will report all incidents of violence as defined herein to the Joint Health and Safety Committee for review.

- The Employer agrees to provide training and information on the prevention of violence to all employees who come into contact with potentially aggressive persons. This training will be done during a new employee’s orientation and updated as required.

- Subject to appropriate legislation, and with the employee’s consent, the Employer will inform the Union within three (3) days of any employee who has been subjected to violence while performing their work. Such information shall be submitted in writing to the Union as soon as practicable.

6.08 The parties agree that if incidents involving aggressive client action occur, such action will be recorded and reviewed at the Joint Health and Safety Committee. Reasonable steps within the control of the Employer will follow to address the legitimate health and safety concerns of employees presented in that forum.

It is understood that all such occurrences will be reviewed at the Resident Care Conference.

9. College of Nurses of Ontario (2017). Refusing Assignments and Discontinuing Nursing Services. Retrieved from: https://www.cno.org/globalassets/docs/prac/41070_refusing.pdf

Section 8 & 9

General Duty to Establish Measures and Procedures

- Every employer in consultation with the joint health and safety committee or health and safety representative, if any, and upon consideration of the recommendation thereof, shall develop, establish and put into effect measures and procedures for the health and safety of workers. O. Reg. 67/93, s. 8.

- (1) The employer shall reduce the measures and procedures for the health and safety of workers established under section 8 to writing and such measures and procedures may deal with, but are not limited to, the following:

-

- Safe work practices.

- Safe working conditions.

- Proper hygiene practices and the use of hygiene facilities.

- The control of infections.

- Immunization and inoculation against infectious diseases.

- The use of appropriate antiseptics, disinfectants and decontaminants.

- The hazards of biological, chemical and physical agents present in the workplace, including the hazards of dispensing or administering such agents.

- Measures to protect workers from exposure to a biological, chemical or physical agent that is or may be a hazard to the reproductive capacity of a worker, the pregnancy of a worker or the nursing of a child of a worker.

- The proper use, maintenance and operation of equipment.

- The reporting of unsafe or defective devices, equipment or work surfaces.

- The purchasing of equipment that is properly designed and constructed.

- The use, wearing and care of personal protective equipment and its limitations.

- The handling, cleaning and disposal of soiled linen, sharp objects and waste.

(2) At least once a year the measures and procedures for the health and safety of workers shall be reviewed and revised in the light of current knowledge and practice.

(3) The review and revision of the measures and procedures shall be done more frequently than annually if,

- the employer, on the advice of the joint health and safety committee or health and safety representative, if any, determines that such review and revision is necessary; or

- there is a change in circumstances that may affect the health and safety of a worker.

(4) The employer, in consultation with and in consideration of the recommendation of the joint health and safety committee or health and safety representative, if any, shall develop, establish and provide training and educational programs in health and safety measures and procedures for workers that are relevant to the workers’ work. O. Reg. 67/93, s. 9.

CNO Practice Guideline – Refusing Assignments and Discontinuing Nursing Services

The CNO has retired this guideline. Please contact your Bargaining Unit President with questions.