Objectives of the Guide

The objectives of Occupational Health and Safety: A Guide for ONA Members are to:

- Provide ONA members with a basic understanding of occupational health and safety law and principles and how they apply to health-care workplaces.

- Empower members with measures they can take, through the rights given to them under the Occupational Health and Safety Act, for the prevention of injuries and the elimination of the hazards in our workplaces.

- Encourage ONA occupational health and safety representatives to take more active roles in promoting health and safety initiatives in their Bargaining Units.

- Provide ONA members with valuable tools and resources to help them deal with occupational health and safety issues and make their workplaces safe and healthy.

Although this guide is very detailed, the information contained is not exhaustive and is intended only to provide general guidance and information about WSIB claims.

How to use this guide:

- Section I: The Internal Responsibility System

- Section II: The Law

- Section III: Hazardous Conditions & Substances

- Section IV: Education and Training

- Section V: Make it work for you

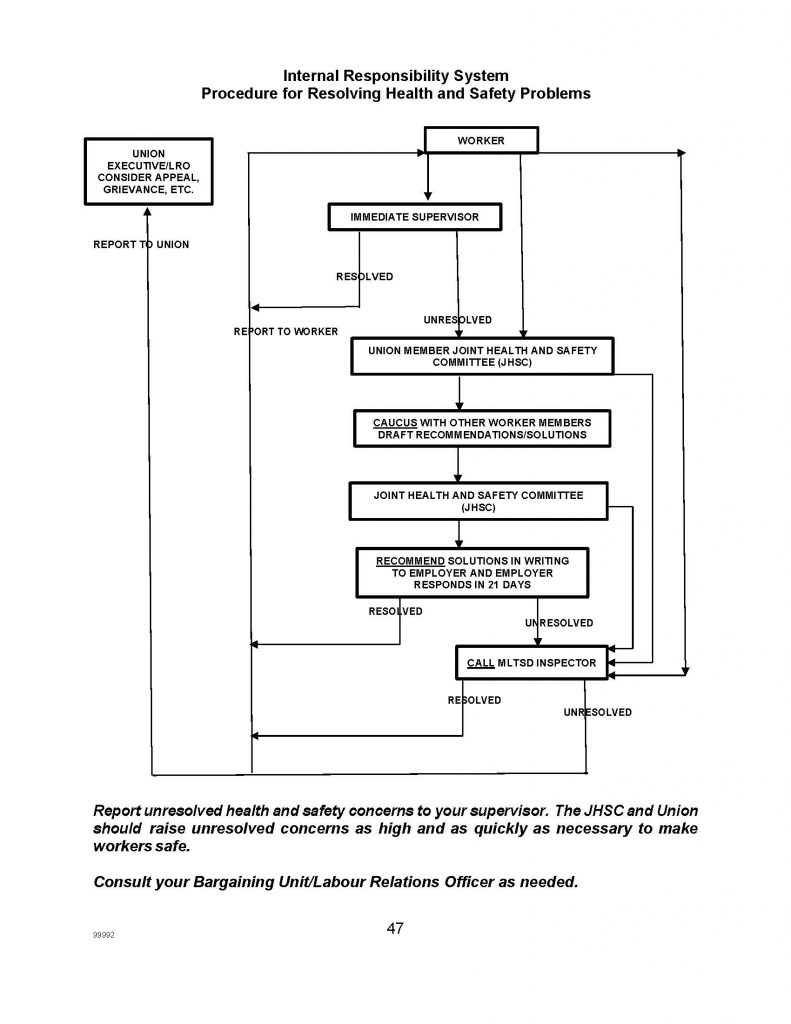

- Resolving health & safety problems

- Sample Scenarios

- Appendix A

- Appendix B

- Appendix C

- Appendix D, E, F

- Appendix G

- Appendix H

- Appendix I

- Appendix J

Occupational Health and Safety and the Internal Responsibility System

Occupational Health and Safety in the Health-care Sector

ONA has battled health and safety problems in health-care facilities for many years. Violence, needlestick injuries, musculoskeletal disorders also known as repetitive strain injuries (RSIs) and exposure to infectious diseases are just some of the health and safety hazards our members face daily and that generate continuously high injury rates in the health-care sector. Speaking to an audience of nurses in May 2005, then Minister of Health George Smitherman explicitly recognized the problems of worker safety in this sector:

One of the things I was struck by…[was] the number of nurses that work in environments, hospital environments most particularly, that actually are unsafe…We have a lot of work to do on that.

We know that even though occupational health and safety legislation has applied to our workplaces since 1979, few health-care employers understand occupational health and safety principles and law, and very few have properly functioning and effective Joint Health and Safety Committees (JHSCs). Our complaints and concerns were resoundingly affirmed by the late Justice Archie Campbell in his final report of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) Commission Inquiry. In January 2007, he wrote:

Hospitals are dangerous workplaces, like mines and factories, yet they lack the basic safety culture and workplace safety systems that have become expected and accepted for many years in Ontario mines and factories and in British Columbia’s hospitals.

The 2007 Coroner’s Inquest into the tragic workplace murder of ONA member Lori Dupont also confirmed that health and safety problems continue in our workplaces requiring changes and attention by employers and government.

ONA has been working diligently to change this state of affairs and entrench health and safety cultures in the health-care sector. We have negotiated occupational health and safety language in collective agreements and have independently, and in collaboration with others, pressed the government to improve laws and increase enforcement. We have launched membership initiatives and training. This is to improve JHSC functioning, to combat violence, infectious disease and other hazards in the workplace, and to return our injured and otherwise disabled members to work that is safe for them to do. Activists have been sharing concerns and strategies for addressing all of these issues. As a result, the government and some employers have listened and we now have more lifting devices, needle safety legislation, government-funded and mandated N95 respirators, Workplace Safety and Insurance Board acknowledgement of the need to apply health and safety law and principles to injured workers, plus the precautionary principle has been enacted in legislation (Health Promotion and Protection Act sec. 77.7 (2)).

With ONA pressure, the Ministry of Labour, Training, and Skills Development (MLTSD) (formerly known as the Ministry of Labour MOL) has been more active in our workplaces. The Ministry has issued thousands of orders addressing all forms of hazards in our workplaces and since 2003, has successfully prosecuted several health-care employers for occupational health and safety infractions.

In facilities that have received enforcement attention, we are seeing the beginnings of health and safety cultures and some decrease in injuries. ONA’s health and safety activists are sharing information/experiences and report successes.

There has been progress, but not enough of it. ONA’s health and safety consciousness has risen with more and more of our members identifying hazards and issues. ONA has pursued even more appeals of MLTSD orders/decisions and called for greater enforcement to protect members. We have posted orders and charges and convictions on our website to let members know what can be done, and to publicize these enforcement actions to promote general deterrence of non- compliant employers throughout the sector.

Unfortunately, the introduction of COVID-19 has reinforced how we need to continuously work to ensure proper protections are in place for health-care workers (HCWs). As Justice Archie Campbell said, “Hospitals are dangerous workplaces;” unfortunately, we learned that his recommendations were not implemented and sustained post-SARS. ONA continues to be at the forefront of advocacy for health and safety, filing grievances, filing appeals at the Ontario Labour Relations Board (OLRB), and lobbying the government for better personal protective equipment (PPE) among other actions. ONA will persist in supporting our H&S activists to build a culture of health and safety in their facilities to ensure we continue to protect the health and safety of all workers.

What is the Internal Responsibility System and where did it originate?

In the 1960s and 1970s, workers became increasingly dissatisfied with the state of health and safety in their workplaces. An important event in Canadian occupational health and safety history occurred in 1974 when Elliot Lake miners, alarmed about the high incidence of lung cancer and silicosis among them, engaged in a strike over health and safety conditions. The Ontario government responded by appointing Dr. James Ham to chair a Royal Commission into health and safety in mines. His 1976 report, known as the Ham Commission Report, is considered a seminal work that led the way to the establishment of the Internal Responsibility System (IRS) as the implicit framework around which all modern Canadian occupational health and safety legislation is built.

The IRS that Ham talked about is a health and safety philosophy based on the principle that every individual in the workplace has a role to play in health and safety. Boards of Directors, Chief Executive Officers, managers and supervisors have the greatest responsibilities. In brief, they must first establish safe and healthy workplace policies and systems. They are responsible to ensure that measures, procedures, equipment and training are in place and supported, and must take “every precaution reasonable in the circumstances to protect” workers. Workers then have the duty to work safely and report hazards. A workplace JHSC, comprised of management and worker representatives who are equals, monitors the state of health and safety and makes recommendations for improvement.

Workplace parties are expected to work toward an equal partnership in matters of health and safety, but equal partnership and an IRS does not develop overnight. It has been suggested that as an IRS improves, the level of compliance will move from enforced compliance, through self- compliance to ethical compliance. In ONA’s experience, health-care employers have been slow to fulfill their duties. The “external responsibility system” of enforcement (primarily by MLTSD inspections, orders and prosecutions) can stimulate a sluggish IRS and motivate employers and can be the catalyst for making employers work with workplace parties to establish safe and healthy workplaces.

What makes an IRS successful?

The Ontario government commissioned an independent review of the MLTSD health and safety division in the 1980s. The Mackenzie Laskin study looked at the IRS and found:

For the system to be effective, the complete line of command, from the Board of Directors through the chief executive, managers, supervisors and workers, must be accountable for health and safety in the workplace. Support from the top is vital; the Chief Executive who sets health and safety as an equal and integral part of the management process, along with productivity and cost control, will achieve direct benefits in the form of a better health and safety record, and indirect benefits through improved morale, employee pride in their company and public recognition.

The investigators further commented that a successful IRS needs:

- Commitment by senior management to provide for meaningful worker participation in health and safety

- Access by workers to relevant information on health and safety

- Education and training on health and safety for workers and management

- Consistent enforcement of the Act and meaningful penalties for those who violate the rules.

Some Concerns about the IRS

ONA supports Internal Responsibility Systems that guarantee workers meaningful and equal participation into the decisions which affect their health, safety and well-being. However, as noted above, the IRS does not happen overnight. Most of our workplaces do not have a mature IRS, and the power imbalance within the workplace does not allow for the equal partnership in health and safety that is central and essential to the IRS philosophy.

Until the workplace IRS is at the “ethical compliance” level (and few if any workplaces realistically reach this pinnacle), workers must continue to rely on the “external responsibility system” of enforced compliance with occupational health and safety law.

Unfortunately, many of our employers do not completely understand the top-down nature of health and safety responsibilities (as per Mackenzie Laskin above) and often tell our members that workers are equally responsible for health and safety in the workplace. They are wrong. Employers have ultimate responsibility for ensuring a safe and healthy workplace. Knowing they will be held accountable for not maintaining a safe and healthy workplace will hopefully force employers to fulfill their responsibilities under the Act. It will also provide good reason for them to deal with the worker committee members in good faith and will, therefore, be conducive to the development of a robust IRS. So ONA views the IRS as a supplement to external enforcement, but not as its substitute.

Accelerating the IRS

Many of the health and safety concerns of ONA members have been taking too long to resolve. Unresolved concerns have spent months and even years on JHSC agendas, with no solutions in sight. Given this experience, ONA recommends that, wherever possible, members should use the basic IRS. There is nothing in the law requiring the IRS to grind slowly. Don’t let issues drag on. Members should report health and safety concerns to their supervisor and, if not resolved, to their JHSC member and the union, who should raise the unresolved concern as high as necessary, as quickly as necessary to protect workers. When internal workplace efforts fail, call the MLTSD. For more information, see Appendix H: “Unresolved Health and Safety Concerns: Guidelines re: When to Call the Ministry of Labour.”

How ONA Activists Can Help

Despite our best efforts, much more needs to be done and we need to equip and motivate our on-the-ground activists to keep up the fight. Preventable hazards continue to plague health-care workplaces and injuries from violence, musculoskeletal disorders and falls outpace much of the rest of the workforce, including manufacturing, construction and mining. The health-care sector leads the workforce in illness from reported exposure to workplace contaminants.

Keep in mind that research conducted by the Director of Engineering Services for the Insurance Company of North America suggests a ratio of accident reporting of 1-10-30-600. That means for every reported disabling injury, there are 10 minor injuries, 30 property damage accidents and 600 incidents with no visible injury or damage (“near-miss” accidents). This ratio does not take into account unreported incidents. It can be said that unreported events need the same attention and focus. It is critical for members to report all events, including the “near misses,” to ensure the contributing factors are investigated and appropriate action is taken to prevent an accident from occurring. Using the theoretical ratio above and the reported accident rate, we can begin to extrapolate the real frequency of these occurrences in health care.

Yet the MLTSD seems to pay disproportionate attention to our sector.

ONA participated in the development of a booklet of advice on the types of approaches that can help health and safety activists make the most impact in their workplaces, “Health and Safety Representation, Writing the Workers Back In,” available on ONA’s website (located at https://www.ona.org/wp-content/uploads/loarc_workersguide_201404.pdf). The guidance is based on research and experience of activists and was prepared by occupational health and safety specialists from unions, the Workers Health & Safety Centre (WHSC) and the Occupational Health Clinics for Ontario Workers (OHCOW). Social science research by a core group of these activists revealed, “Ten Operating Principles for Guiding Effective Participation.” (Excerpted as Appendix J in this booklet).

The Law

The Occupational Health and Safety Act

The Occupational Health and Safety Act (the Act) was first passed in 1979 and applies to most workers and workplaces in Ontario. It is designed to protect workers against health and safety hazards in the workplace.

The Act has undergone many amendments since its enactment, but the basic structure and purpose remains unchanged. It sets out general principles and duties for employers, the JHSC, workers and other parties to promote healthy and safe workplaces in Ontario. Individuals, including directors and officers of corporations, face maximum fines of up to $100,000 and imprisonment of up to 12 months, and corporations can be fined up to a maximum of $1,500,000 if found in violation of the Act or its regulations (Section 66).

Regulations

The Occupational Health and Safety Act also gives the Ontario government the power to make regulations, which are more detailed instructions on how the duties of workplace parties are to be carried out. When the first Act was passed in 1979, regulations for industrial establishments, construction projects and mines also came into effect. Since that time, several changes have been made to existing regulations, and additional regulations have been put in force.

In 1993, a regulation for the health-care sector, called the Regulation for Health Care and Residential Facilities, came into effect. Although a draft regulation for the health-care sector was initially completed in 1987 through the efforts of a bipartite committee of labour and management, passage of the regulation had been stalled over government concerns about costs and opposition from the Ontario Hospital Association (OHA). When the provincial government re-opened discussions on the draft regulation in 1991, labour representatives at the table were dismayed to find that many of the provisions of the 1987 draft, which had been determined through a consensus process, were up for discussion again.

Despite the provincial government’s claim of a commitment to occupational health and safety, the end result of this next round of discussions was disappointing. When the new regulation was finally proclaimed early in 1993, important sections were completely left out and other sections were weakened and, therefore, offered less protection. Since then, we have fought to secure legislation to better protect our members, such as needle safety regulations, violence prevention provisions and amendments to the work refusal section of the Act. In September 2016, there were further amendments to the Act expanding employer duties regarding workplace harassment and defining “sexual harassment” as a type of workplace harassment. The violence and harassment provisions still are not perfect, and ONA continues its efforts to ensure there is adequate law to protect our members, and that it is appropriately enforced.

Use the tools and resources in this booklet and the ONA companion booklet Violence in the Workplace, and on the ONA website (www.ona.org) to assist in efforts to enforce these and other parts of the legislation.

Regulation for Health Care and Residential Facilities

This regulation applies to the following types of facilities including, but not limited to:

- A hospital as defined in the Public Hospitals Act or the Community Psychiatric Hospitals Act.

- A laboratory or specimen collection centre as defined in the Laboratory and Specimen Collection Centre Licensing Act.

- A private hospital as defined in the Private Hospitals Act.

- A psychiatric facility as defined in the Mental Health Act.

- A long-term care home as defined in the Long-term Care Homes Act.

- A supported group living residence.

Most other health-care facilities not listed above should be covered under the Industrial Establishments Regulation 851 (see below).

The health-care regulation sets out the employer’s obligation to develop measures and procedures in consultation with the JHSC (Section 8 and 9). The obligation for the employer to develop a written occupational health and safety policy already exists under the Act, but the only regulation in which the measures and procedures to implement the policy are reinforced is the regulation for health care in which there is a list of specific measures and procedures to be addressed. Among other things, the list includes:

- Safe work practices.

- Safe working conditions.

- Proper hygiene practices.

- Control of infections.

- Immunization and inoculation against infectious diseases.

- Biological, chemical and physical hazards.

- The handling, cleaning and disposal of soiled linen, sharps and waste.

The health-care regulation has similarities to the regulation for industrial facilities in that it covers comparable areas, e.g., the requirements for work with scaffolding, and rules about operating machinery, ladders, material lifting equipment, explosives and other hazards associated with work in an industrial setting.

However, O. Reg 420/21, Notices and Reports Under Sections 51 To 53.1 of the Act – Fatalities, Critical Injuries, Occupational Illnesses and Other Incidents states what details an employer must include in reports to the MLTSD concerning workplace injuries and fatalities. These reports are required under Section 51-53 of the OHSA, and the regulation lists mandatory details, such as names and addresses of victims, witnesses, and steps taken to prevent a recurrence.

The health-care regulation also contains detailed rules on hazards specific to health-care facilities, such as:

- Anesthetic gases.

- Antineoplastic drugs.

- Housekeeping and waste.

Section 96 on anesthetic gases outlines the employer’s obligation:

- To install effective scavenging systems to collect, remove and dispose of waste anesthetic gases.

- Install anesthesia machines to reduce contamination of air in the room during administration of anesthetic gases.

- Implement a program to inspect and maintain scavenging systems and anesthesia machines.

- To adopt work practices to reduce contamination of room air with anesthesia

- For the regular maintenance of ventilation systems, including filters.

The regulation does not explicitly require regular air monitoring for anesthetic gas levels, although an earlier draft of the legislation called for monitoring at three-month intervals and whenever requested by workers in those areas.

Section 97 on antineoplastic drugs requires the employer in consultation with the JHSC to develop written measures and procedures to protect workers who may be exposed to antineoplastic agents or material, or equipment contaminated by those agents. Procedures shall include:

Procedures for normal storage, preparation, handling, usage, transportation, and disposal of the drugs and drug-contaminated materials.

- Emergency procedures to be followed if a worker is exposed to the dug.

- Maintenance and disposal of equipment contaminated with antineoplastic agents.

- Measures for the use of engineering controls, work practices and appropriate personal protective equipment

- An appropriate biological safety cabinet for the preparation of antineoplastic drugs.

The section also obliges the employer to provide training and instruction in these measures and procedures to workers who may be exposed to antineoplastic drugs.

Sections 113 and 114 deal specifically with the disposal of sharps and the issue of recapping needles. Section 113 defines “sharps” as “needles, knives, scissors, scalpels, broken glass or other sharp objects” and says these must be discarded in puncture-resistant containers.

Section 114 requires that used needles be discarded immediately after use, without being bent or recapped, into a puncture-resistant container. It does allow for the possibility that there are times when immediate disposal of a used needle into a puncture-proof container may not be practicable. In these cases, the regulation allows for workers to use an employer-provided device to recap needles “that protects workers from being accidentally punctured while they are recapping.” Workers using such devices must be instructed and trained in their use, and although the employer may choose the device, this must be done in consultation with the JHSC or health and safety representative (see also section on “Needle Safety” below).

Regulation for Industrial Establishments

ONA believes this regulation covers virtually all ONA workplaces that are not captured under the facilities identified in Regulation for Health Care and Residential Facilities above. This industrial regulation was one of the original regulations written under the Act, and pre-dated the health care regulation by more than a decade. This regulation applies to a wide variety of workplaces, including factories, shops, offices and arenas, and is heavily oriented to industry. The industrial regulation usually covers health care facilities, such as public health units, community nursing, and blood clinics. While the Regulation for Health Care and Residential Facilities does not automatically apply to such workplaces, it is often argued that the provisions of the health care regulation are “reasonable precautions” to take in any health care workplace, and thus by extension, they too have application to health care workplaces covered by the Regulation for Industrial Establishments.

Needle Safety

A Needle Safety Regulation (O. Reg. 474/07) mandating the use of safety-engineered needles (SENs) or needleless systems to replace hollow-bore needles in hospitals came into effect September 1, 2008. The regulation provides some exceptions to the requirement, and the government has since extended the requirements to long-term care homes, psychiatric facilities, laboratories and specimen collection centres and other health care workplaces, (e.g. home care, doctors’ offices, ambulances, etc.). This legislation applies in addition to the Act and the pertinent provisions of the health care regulation explained above to address health and safety concerns about sharps.

Biological and Chemical Regulations

There are also regulations in place to control toxic substances in the workplace, the presence or use of which may endanger the health or safety of a worker. Regulation 833 – having a hard time finding this controls exposure and sets limits in workplace air for approximately 600 specific biological and chemical agents.

The other approach used by the MLTSD has been to develop a regulation specific to particular toxic substances, such as asbestos, mercury and ethylene oxide. These substances are known as designated substances. Originally, each designated substance had its own regulation, but in 2009 they were consolidated into a single “Designated Substances” regulation 490/09. The regulation contains provisions for an assessment of the likelihood of worker exposure in the workplace and a control program, which includes provisions for engineering controls, work practice, hygiene practices, air monitoring, record keeping and medical surveillance.

Critical Injury – Defined

O.Reg 420/21 – Notices And Reports Under Sections 51 To 53.1 of the Act – Fatalities, Critical Injuries, Occupational Illnesses And Other Incidents defines “critical injury.” There are stricter notice deadlines under Section 51 of the OHSA (immediate verbal notice and 48-hour written notice) for “critical” (and fatal) injuries, than there are for other disabling injuries and illnesses under OHSA Sections 52 (four days) and project or mine events under OHSA Section 53 (two days). Also, a worker member of the JHSC is entitled to investigate “critical” injuries (OHSA Section 9 (31)).

Other Laws

Other pertinent legislative documents members may need to use are:

- Ambulance Act.

- Atomic Energy Control Act.

- Building Code Act.

- Compensation for Victims of Crime Act.

- Criminal Code of Canada.

- Dangerous Goods Transportation Act.

- Environmental Protection Act.

- Fire Protection and Prevention Act and Fire Code.

- Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act.

- Healing Arts Radiation Protection Act.

- Health Protection and Promotion Act.

- Laboratory and Specimen Collection Centre Licensing Act.

- Long-Term Care Homes Act.

- Mental Health Act.

- Occupier’s Liability Act.

- Ontario Human Rights Code.

- Private Hospitals Act.

- Public Hospitals Act.

- Regulated Health Professions Act.

- Transportation of Dangerous Goods Act.

- Workplace Hazardous Materials Information System (WHMIS) Regulation 860.

- Workplace Safety and Insurance Act.

- X-ray Safety Regulation 861.

Workers’ Rights under the Act

The “Three Rights”

In Ontario, Ham’s report led to the enactment in 1978 of the current Occupational Health and Safety Act, which legislated JHSCs and also embodied what has become known as the “three rights” i.e. the workers’ right to know, to participate and to refuse unsafe work. While not explicitly written, these principles are manifested in various sections of the Act.

Right to Know

Workers have a basic right under Section 25 of the Act to know exactly what hazards they are being exposed to at work. Generally, the employer must provide workers and their JHSC or health and safety representative (in workplaces with six to 19 workers) with information and instructions in addressing and improving workplace health and safety. Specifically, all hazardous articles, devices, equipment and biological chemical and physical agents must be identified (Section 37 (1)) and workers must be instructed on how to use, handle and store them safely (Section 37 (3)). For instance, Section 97 of the Health Care Residential Facilities Regulation obligates the employer to provide written instructions to workers with regard to the handling of antineoplastic drugs. Section 9 (4) of the Health Care Residential Facilities Regulation (applicable to hospital and LTCH employers) also requires these employers in consultation with the Joint Health and Safety Committee (JHSC) or Health and Safety Representative to develop, establish and provide training and educational programs in health and safety measures and procedures for workers that are relevant to the worker’s work. Therefore, merely providing information or a few instructions is not sufficient and would not comply with this provision of the regulation.

OHSA Section 32.0.5 (3) states it is the employer’s duty to provide information about violence to a worker under clause 25 (2) (a) and a supervisor’s duty to advise a worker under clause 27 (2) (a). This includes providing personal information related to a risk of workplace violence from a person with a history of violent behaviour if the worker can be expected to encounter that person in the course of their work and if the risk of workplace violence is likely to expose the worker to physical injury.

The Occupational Health and Safety Act and any explanatory material must be posted in the workplace, both in English and the majority language of the workplace (Section 25 (2) (i)). Workers are also entitled to copies of inspectors’ reports and orders (Section 57 (10)), air sampling results, an annual Workplace Safety and Insurance Board (WSIB) summary of deaths, injury and occupational illness in the workplace (Section 12), and any other reports concerning health and safety in that workplace (Section 9, 25 (2) (l) & (m), 51, 52, 53, 59).

Workplace Hazardous Materials Information System (WHMIS)

The “Right to Know” provisions of the Act include language under “Part IV – Toxic Substances,” which establishes the WHMIS. A WHMIS regulation clarifies in detail the provisions in the Act. Since February, 2015 WHMIS across Canada has been undergoing revisions to align it with new international standards for classifying hazardous chemicals and providing information on labels and safety data sheets.

The three major components of WHMIS legislation continue to be:

- Comprehensive labeling of all hazardous materials.

- Provision of Safety Data Sheets (SDS) containing detailed information about the properties of substances, their potential hazards and safe ways of handling such materials.

- Training of workers and supervisors who are exposed or likely to be exposed to hazardous materials or who use these materials in their work.

The main differences are that “controlled products” are now “hazardous products” and as described on the Ontario MLTSD website there are:

- New rules for classifying hazardous workplace chemicals.

- Two main hazard classes – physical hazards and health hazards.

- New label requirements including pictograms instead of symbols that correspond to hazard classes; and

- A different format for safety data sheets.

The key responsibilities of suppliers, employers and workers are the same under WHMIS 2015.

The Globally Harmonized System (GHS) for Hazard Communication is an internationally-accepted standard for the identification of health, physical and environmental hazards in the workplace.

Right to Participate

As explained above, the philosophy underpinning the Occupational Health and Safety Act is known as the “Internal Responsibility System” (IRS). This system assigns authority over occupational health and safety in the workplace to the management, but all workplace parties should be involved in the protection of their health and safety. Workers have responsibilities to work safely. In addition, workers, particularly those selected by the union(s) in the workplace to sit on the JHSC, have an opportunity to shape the health and safety environment in their workplace. The JHSC is the driving force of the IRS in the workplace and the Act confers several powers to facilitate worker participation in workplace health and safety, including, but not limited to:

- Workers select at least half of the JHSC members and a co-chair (Sec. 9 (7) (8)(11)).

- Receive paid time to caucus before meetings, meet and perform JHSC duties (Sec. 9 (34) (35)).

- Write recommendations (Sec. 9 (18)).

- Be present at the beginning of testing (Sec. 9 (18)).

- Inspect the workplace at least once a month (Sec. 9 (26)).

- Investigate fatal and critical injuries (Sec. 9 (31)).

- Accompany an inspector (Sec. 54 (3)).

Without a competent, effective JHSC with the active and sustained participation of workers, the occupational health and safety of the workers in the workplace may be severely compromised.

Right to Refuse or Stop Unsafe Work

The Act provides a conditional “Right to Refuse” unsafe work for health-care workers (Section 43). Health-care workers who work in institutions can refuse unsafe work only when the life, health or safety of another person or the public is not directly in danger.

This conditional Right to Refuse applies to police officers, firefighters, ambulance workers and some other groups of workers who care for the public. The majority of Ontario workers do not have this condition put on their right to protect their own safety in the workplace. Even some health-care workers, such as community health nurses who work outside institutions, have no statutory limitation put on their right to refuse unsafe work. However, there may be consequences related to regulatory body (i.e. CNO) standards.

Certainly no health-care worker wants to jeopardize the life, health or safety of another person, but neither should they be expected by the employer to needlessly jeopardize their own safety. See the ONA guide My Right to Refuse Unsafe Work: A Guide for ONA Members for detailed information about an individual worker’s right to refuse unsafe work. This guide can also be downloaded from ONA website (visit www.ona.org and go to the health and safety section).

The Act also provides a conditional “Right to Stop Dangerous Work” to health-care workers (Section 44-47). Designated JHSC members may initiate a work stoppage, but only in “dangerous circumstances” (Section 44(1)), which means a situation in which all of the following are true:

- The Act or the regulations are being violated.

- The violation poses a danger or a hazard to a worker.

- Delay in controlling the danger or hazard may seriously endanger a worker.

In most cases, it takes two certified members to direct an employer to stop dangerous work. One must be a certified member representing workers, the other a certified member representing the employer. In some special cases, a single certified member may have this right. Sections 45, 46 and 47 of the Act set out the procedure for exercising this right.

The same limitations apply to this right as to the “Right to Refuse” that is, health-care workers and others who work in a variety of health-care facilities cannot initiate a work stoppage if doing so will endanger the life, health or safety of another person (Section 44(2)). This legal condition restricts the rights of health-care workers to stop dangerous work, so if in doubt, members should consult their Bargaining Unit/Labour Relations Officer and their ONA JHSC member or call the MLTSD. (See My Right to Refuse Unsafe Work: A Guide for ONA Members that can be found on the ONA website at www.ona.org)

SARS and the Fourth Right

The rights of workers to know, participate and refuse unsafe work arose from the Ham Commission inquiry into health and safety in mines. Justice Campbell’s SARS Commission findings about health and safety in the health-care sector has suggested a fourth worker’s right: the right to have the “precautionary principle” applied to health and safety in our workplaces.

In the spring of 2003, SARS swept through Ontario, causing 44 deaths and hundreds of cases of lung disease. The province suffered, but the health-care system, particularly in Toronto, was devastated. The government appointed Justice Archie Campbell of the Superior Court of Justice to lead an independent investigation into SARS. Justice Campbell relied heavily on ONA members’ evidence and was open in his praise for the courage of ONA members and other health- care workers who persevered through the crisis. We owe a debt of gratitude to Justice Campbell for his work. His final report, containing more than 80 recommendations, is every bit as important to workplace safety as the work of Dr. Ham in the 1970s.

Justice Campbell’s key recommendation or “take-home message” was the need for adoption of the “precautionary principle, which states that action to reduce risk need not await scientific certainty.” He recommended that it:

be expressly adopted as a guiding principle throughout Ontario’s health, public health and worker safety systems by way of policy statement, by explicit reference in all relevant operational standards and directions, and by way of inclusion, through preamble, statement of principle, or otherwise, in the Occupational Health and Safety Act, the Health Protection and Promotion Act, and all relevant health statutes and regulations.

Calling this, “…the most important lesson of SARS,” he said, “we should not be driven by the scientific dogma of yesterday or even the scientific dogma of today. We should be driven by the precautionary principle that reasonable steps to reduce risk should not await scientific certainty.”

ONA secured an initial victory in 2007 by convincing the government to insert the precautionary principle into the Health Protection and Promotion Act. As a result, now when issuing a directive involving an outbreak, the Chief Medical Officer of Health:

“shall consider the precautionary principle where, b) the proposed directive relates to worker health and safety in the use of any protective clothing, equipment or device” (section 77.7 (2)).

In accordance with the precautionary principle, ONA also convinced the government to mandate the use of and supply N95 respirators in preparation for a pandemic. ONA has also negotiated precautionary principle and N95 respirator language into the Hospital Central and other collective agreements.

This is progress, but not perfection. For the protection of our members and as a tribute to Justice Campbell and his legacy, ONA continues in its efforts to have the precautionary principle widely adopted, and to ensure that the rest of his sage recommendations are implemented.

The Internal Responsibility System within the Occupational Health and Safety Act

The IRS is not overtly mentioned in the Occupational Health and Safety Act, but as discussed above, it is implicit in the Act. The Act gives everyone responsibility for health and safety by assigning specific duties to employers, supervisors, workers and other workplace parties.

In brief:

- Employers are legally required to establish a health and safety policy and program and a safe working environment, ensure every reasonable safety and health precaution is taken to protect workers and ensure supervisors are “competent,” e. familiar with health and safety legislation and have knowledge of potential or actual dangers to health and safety in the workplace.

- Supervisors must ensure the workplace is safe, workers are working safely, every precaution reasonable in the circumstances is taken to protect workers, and any concerns that come to their attention are

- Workers must work safely and report hazards.

- JHSC should address unresolved health and safety concerns and, where appropriate, should:

- CAUCUS with other worker members before every JHSC meeting to discuss concerns, share information and develop written recommendations to present to the committee as a whole (see Appendix D for memo confirming joint union intention for health care unions to work together).

- RECOMMEND actions/solutions in writing to the employer, who has 21 days to respond in writing with a timetable for implementation and reasons for any denial.

- CALL THE MLTSD if a concern cannot be resolved through this IRS (e.g. employer rejects recommendations in whole or part or response is not satisfactory). The MLTSD may issue orders and/or prosecute if there is a violation of the Act or the regulations.

As previously mentioned, don’t let issues drag on. The JHSC should raise unresolved health and safety concerns as high as necessary, as quickly as necessary. When internal workplace efforts fail, call the MLTSD (for more information see Appendix H: “Unresolved Health and Safety Concerns: Guidelines re: When to Call the Ministry of Labour”).

The following sections provide short summaries of parts of the legislation that assign responsibilities and functions to the various participants in the IRS. Please refer to the actual legislation for exact and accurate language.

Duties of the Employer under the Act

(Reference: Section 25 of the Occupational Health and Safety Act)

- Provide information, instruction and supervision to a worker to protect the health or safety of that worker.

- Provide, upon request, information including confidential business information, to a legally qualified medical practitioner in a medical emergency for the purpose of diagnosis or treatment.

- Appoint a competent person to serve as supervisor. “Supervisor” has a specific definition in this At times ONA members, who for instance act as charge nurses or “in-charge or a variety of other positions, either permanent or temporary) may fall within this definition and therefore have the personal legal duties and liabilities of a “supervisor”. “Competent person” has a specific meaning under the Act. A “competent person” is one who must:

- Be qualified through knowledge, training and experience to organize the work and its performance.

- Be familiar with the Act and the regulations that apply to the work being performed in the workplace.

- Know about any actual or potential danger to health and safety in the workplace.

- It is the employer’s duty to ensure that anyone acting in a “supervisor” role in the workplace is trained to meet these legislated requirements to qualify as “competent persons.”

- Acquaint a worker or a person in authority over a worker with any hazard in the work and in the handling, storage, use, disposal and transportation of any article, device, equipment or a biological, chemical or physical agent.

- Offer assistance and cooperation to a committee or a health and safety representative in carrying out their functions.

- Employ in or about a workplace only a person over such an age as may be prescribed.

- Take every precaution reasonable in the circumstances for the protection of a worker.

- Post in the workplace a copy of the Act and any explanatory material prepared by the MLTSD, both in English and the majority language of the workplace, outlining the rights, responsibilities and duties of workers.

- Prepare and (at least) annually review a written occupational health and safety policy and develop/maintain a program to implement that policy, in consultation with the JHSC. Employers are also required to post the policy and provide copies to the JHSC or health and safety representative (Sections 25 (2)(j)(k) of the Act and Sections 8 and 9 of the Regulation for Health Care and Residential Facilities).

- Provide the JHSC or the health and safety representative with the results of any occupational health and safety report the employer has. If the report is in writing, the employer must also provide a copy of the relevant parts of the report.

- Advise workers of the results of such a If the report is in writing, the employer must, on request, make available to workers copies of the portions that concern occupational health and safety.

- Ensure that all equipment required by the Act or regulations is provided, maintained in good condition and used properly by workers.

- Ensure that measures and procedures required by the Act and regulations and employer policy are carried out.

Additional responsibilities of the employer may be found in other sections of the Act:

- Provide a written response to a JHSC or either of the JHSC co-chair’s written recommendations within 21 days. The written response must contain a timetable for implementation and provide reasons for disagreeing with any recommendations (Section 9 (20) (21)). (As a result of a 2011 amendment to the Act, when good faith attempts to reach consensus fail, either co-chair has the power to make written recommendations (Section 9 (19.1) that trigger the duty of the employer to respond in writing within 21 days of receipt of the recommendation.)

- Establish a medical surveillance program for workers as prescribed and provide for safety- related medical exams and tests, and related expenses and wages (Section 26 (1) (h) (i) (3)).

- Prepare policies and programs on workplace violence and harassment, and assess and reassess the risk of violence as often as necessary to ensure the violence policy and program continue to protect workers from workplace (Sections 32.0.1 – 32.0.8)

- Notify the MLTSD, JHSC, health and safety representative and trade unions within 48 hours when a worker is critically injured or killed (Section 51).

- Notify the MLTSD (if required), JHSC, health and safety representative and trade unions within four days when a worker is disabled or requires medical attention resulting from an accident, fire or explosion or incident of workplace violence (Section 52 (1)).

- Notify the MLTSD, JHSC, health and safety representative and trade unions within four days of being advised of an occupational illness (Section 52 (2) (3)).

- Where a notice or report is not required under Section 51 or 52 and an accident, premature or unexpected explosion, fire, flood or inrush of water, failure of any equipment, machine, device, article or thing, cave-in, occurs at a construction project, notify the MLTSD, JHSC, health and safety representative and trade unions in writing within two days of the occurrence (Section 53).

- Afford a worker JHSC member an opportunity to accompany an inspector during a physical inspection of the workplace (Section 54 (3)).

- Provide the JHSC and health and safety representative with copies when the Ministry inspector finds violations of legislation and issues order(s) (Section 57 (10)).

Employer Reprisals

Employers are prohibited by Section 50 of the Act from taking any disciplinary action against an employee or intimidating them because they worked in compliance with the Act, the regulations or an order made under the Act. Employees are also protected by the Act if they are seeking enforcement of the Act or its regulations. If an employer does violate the Act and takes prohibited action against a worker, the worker has the option of filing a grievance under the collective agreement and having the matter dealt with by final and binding arbitration, or by filing a complaint with the Ontario Labour Relations Board.

Duties of the Supervisor under the Act

(Reference: Section 27 of the Occupational Health and Safety Act)

- Advise a worker of the existence of any potential or actual danger to the health or safety of the worker of which the supervisor is aware.

- Take every precaution reasonable in the circumstances for the protection of the worker.

- Ensure that a worker works in the manner and with the protective devices, measures and procedures required by the Act and the regulations.

- Ensure that a worker uses or wears the equipment, protective devices or clothing the employer requires.

- Provide a worker with written instructions regarding measures or procedures to be taken for the protection of the worker, where prescribed.

It is essential that supervisors fully understand their duties under the Act in order to properly address our members’ health and safety concerns. Employers have a responsibility under the Act to ensure that all its supervisors are competent. Nurses, like many other unionized professionals, often end up directing or supervising other workers. ONA therefore expects and requests that all employers provide full training for all supervisors, including ONA members working in a supervisory capacity (as defined in the Act) on matters within their responsibility. This must include ensuring that the workplace has a full set of policies and protocols for handling all potential health and safety situations and concerns, and ensuring that supervisors are fully trained in their application.

The Public Services Health and Safety Association (PSHSA) and the Workers Health and Safety Centre (WHSC) have courses in supervisor competency, as do other providers. Where lacking, the JHSC or either co-chair can make a written recommendation to the employer to provide the needed training to make supervisors “competent” under the Act. For sample recommendations, see Appendix B.

Duties of the Worker under the Act

(Reference: Section 28 of the Occupational Health and Safety Act)

- Work in compliance with the provisions of the Act and the

- Use or wear the equipment, protective devices or clothing the employer

- Report to the employer or supervisor the absence of/or defect in any equipment or protective device of which they are aware and which may endanger themselves or another worker.

- Report to the employer or supervisor any contravention of the Act or the regulations or the existence of any hazard of which they (See Health Safety Hazard Report Form).

- Do not remove or make ineffective any protective device required by the regulations or the employer without providing an adequate temporary protective device, and when the need for removing or making ineffective the protective device has ceased, replace the protective device

- Do not use or operate any equipment, machine, device or thing, or work in a manner that may endanger themselves or any other

Duties of Directors and Officers of a Corporation

(Reference: Section 32 of the Occupational Health and Safety Act)

- Take all reasonable care to ensure that the corporation complies with the legislation and orders and requirements of inspectors, directors and the

Courts expect directors to “immediately and personally react when they have notice that the system has failed” (Making Lemonade out of Lemons, Ontario Federation of Labour, May 2007, page 6). Many corporate leaders aware of these responsibilities have signed on to a national Health and Safety Leadership Charter to provide mutual support and encouragement in meeting workplace health and safety challenges.

A similar awareness is not widespread among board members and executives in Ontario’s health care sector. When the Internal Responsibility System in a workplace breaks down, unions can write to boards of directors explaining the unresolved health and safety concerns in the workplace and pointing out the board members’ personal, individual responsibility to take steps to rectify the situation (for a sample letter, see Appendix C or log onto the members’ section of the ONA website at www.ona.org and follow the links to the health and safety section).

Structure and Functions of the Joint Health and Safety Committee and the Role of the Worker Member

(Reference: Sections 8 and 9 of the Occupational Health and Safety Act)

Structure

- The Act requires workplaces with 20 to 49 employees to have a JHSC (Section 9 (2)) with a minimum of two members on the Where 50 or more workers are employed, the committee must have at least four members. Workplaces with between five and 20 employees are required to select an employee health and safety representative.

- The Minister of Labour may order one JHSC for a multi-site facility (Section 9 (3.1)).

- At workplaces with less than 20 workers, but more than five, a JHSC is not required, but the workers must select at least one non-management health and safety representative from among them (Section 8 (1)). The designated health and safety representative has similar rights and powers as JHSC members (Section 8).

- At least half of the JHSC members shall be workers who do not exercise managerial functions, selected by the union(s) in the

- Management and worker representatives on the JHSC shall each designate one of their members to act as a co-chairperson.

- At least two committee members – one representing the employer and one representing workers – must be chosen for training to become Certified members have specific authority and responsibilities and play a key role on the committee (see the section on “Certification Training,” below). Some unions bargain for greater representation. ONA’s hospital central agreement has a provision requiring certification training for all ONA JHSC members upon written request (article 6.05 (a) (ix)). Members should check their respective collective agreements to see if they are entitled to similar enhancements in their workplaces, and/or negotiate similar provisions.

- JHSC meetings must be held at least every three months, *but often are held

*Meetings may also be convened at the call of either co-chairperson.

- *Guests may be invited to attend a meeting with prior notice and the agreement of both co- chairpersons.

- Worker members will be given time from work to attend all meetings of the All time spent attending JHSC meetings will be considered as work time and members will be paid for this time at their regular or premium rate, as may be appropriate.

- All members of the JHSC should be given paid time off work, as necessary, to carry out their responsibilities between regular committee

- Preparation time, one hour in duration or longer as the committee determines, should be provided as necessary to all members of the JHSC to prepare for a committee Committee members will be paid for this time. Worker members should use this time to caucus with other members from ONA and other unions to discuss issues and prepare written recommendations to table at the main committee meeting.

- The names and work locations of the committee members must be posted in the workplace, where they are most likely to be seen by the The employer is responsible for posting this information.

- Recommendations only; not explicitly mandated by

Functions

- Identify and make recommendations on situations that may be a source of danger or hazard to workers and recommend improvements pertaining to the health and safety of workers in the An employer who receives a written recommendation from the committee, or either co-chair following failure of good faith attempts to reach consensus of the committee, must respond in writing within 21 days. The response must include a timetable for implementing the recommendations. The employer is obliged to provide written reasons for not accepting any recommendations.

- Recommend to the employer, the establishment, maintenance and monitoring of programs, measures and procedures for health and safety in the

- Obtain information from the employer regarding identification of potential or existing hazards and health and safety experience, as well as practices and standards in similar workplaces (Section 9 (18) (d)).

- Obtain information and be consulted about the conducting or taking of tests of any equipment, machine, device, article, thing, material or biological, chemical or physical One of the committee members present at the beginning of testing will be a worker representative (Section9 (18) (f), 11).

- Inspect the workplace at least once a month (worker member designated by JHSC worker members). In many of our workplaces only a portion of the workplace is being inspected monthly versus inspecting the entire workplace. These employers are telling the JHSC worker members that it is not possible to inspect an entire hospital/workplace monthly given its The Occupational Health and Safety Act states “If it is not practical to inspect the workplace at least once a month, the member designated under subsection (23) shall inspect the physical condition of the workplace at least once a year, inspecting at least a part of the workplace in each month.” The question then is, what does “not practical mean”? The MLTSD historically has taken the position that almost all workplaces, including hospitals are not too large to inspect the entire workplace monthly. Therefore, to ensure hazards are being identified and resolved in a timely fashion it is ONA’s position that our ONA JHSC members should be asserting to the employer that it is in fact practical to inspect the entire workplace monthly so long as the employer provides the designated worker member with the time off to do so. If the worker members of the JHSC meet resistance and the employer will not pay for time off to inspect the entire workplace monthly, please contact the MLTSD to file a complaint and advise your Bargaining Unit President and/or LRO that you have done so. Keep in mind, according to the OHSA a worker member of the JHSC will be given time to inspect the workplace. The worker member will be supplied with necessary information and assistance as required for the purpose of carrying out an inspection of the workplace. In multi-site facilities with a single Minister-ordered JHSC, the Minister may permit the worker members of the committee to designate a non-member to conduct inspections (Section 9 (3.2)).

- Participate in designated substance assessments and in the development of control programs under these

- Be consulted by the employer about the development and maintenance of a program regarding workplace harassment (Section 0.6 (1)).

- Request, receive and review Safety Data Sheets (SDS) for hazardous substances used in the

- Be consulted by the employer about making SDSs available in the workplace (Section 38 (6)).

- Be consulted by the employer about the development and implementation and annual review of instruction and training required for a worker exposed or likely to be exposed to a hazardous material or hazardous physical agent (Section 42).

- Review accident and illness reports and statistics and other related information, with a view to preventing future occurrences (Section 12, 51, 52, 53, Occupational Health and Safety Act (OHSA) and Section 3, Notices and Reports Under Sections 51 To 53.1 of the Act – Fatalities, Critical Injuries, Occupational Illnesses And Other Incidents). Many health care employers have not been meeting their reporting obligations and in many cases have only provided the JHSC with summaries of accidents. Many have wrongly claimed they cannot comply because of privacy If your employer refuses to provide you with the information prescribed by Section 3 of the regulation within the time limits set out in Sections 51-53 of the Act, refer them to the MLTSD letter found in Appendix A. If the employer still refuses to provide the required information, call the Ministry of Labour, in consultation with your Bargaining Unit President and Labour Relations Officer.

- Receive and review the results of all inspections and monitor assessment and investigation reports.

- *Ensure the education of workers on safe practices and hazards of the

- *Receive and review new health and safety directives, policies and procedures issued by the government.

- *Review studies and programs regarding occupational health and safety

- Identify issues appropriate for discussion by the

- *Develop a strategy for the provision of information to all levels of

*Recommendations only; not explicitly mandated by legislation.

Worker Member

- The inspecting worker member will inform the JHSC of situations that may be a source of danger or hazard to workers and the committee will consider such information within a reasonable period of

- A worker member(s) of the JHSC will be designated to investigate fatalities and critical injuries. The member(s) chosen to investigate can inspect the actual scene of the accident, but cannot alter it without permission from an They can also inspect any machine, equipment, substance, etc. that may be connected with the accident. They also may question witnesses to the accident, if those persons are willing to be interviewed by the designated worker member.

- A designated worker member will review investigation reports of all fatal and critical injuries and illnesses, and report the findings to the committee who should develop recommendations for future

- *A designated worker member should be given time to assist management in the investigation of all lost time due to workplace injuries and illnesses, and any “near misses,” which are potentially

- A worker member or members of the JHSC will be given time from work to accompany MLTSD officials during inspections and investigations of the

- A worker member will be given time to be present at any investigation into a work refusal and will attend such an investigation without

*Recommendations only; not explicitly mandated by legislation.

Worker Inspections of the Workplace

- The Occupational Health and Safety Act provides the right to designated worker members of the JHSC to inspect the These inspections should be carried out at least once a month.

- In multi-site facilities with a single Minister-ordered JHSC, the worker members of the committee may be advised to designate a non-member to conduct inspections. That designate would have all the powers and rights of a JHSC member (Section 9 (3.2) (3.3)).

Inspection Guidelines

- In some facilities, inspections may be performed by an inspection team consisting of representatives from both management and An arrangement such as this may be set out in the committee’s “Terms of Reference,” which details rules governing the work of the committee. However, the Act requires only that a committee member representing workers perform the inspection (Section 9(23) (26)). And there is no requirement in the OHSA for a committee to have “Terms of Reference.” (For a sample “Terms of Reference,” see Health and Safety section of ONA website at www.ona.org)

- The inspecting worker should identify safety hazards and health hazards present in the workplace and report to a supervisor before leaving the They should review the unit’s accident/injury reports (to which they are entitled) before conducting an inspection as they are a good starting point for determining the most pressing problems in an area. As well, they should be aware of recent staff concerns that have been communicated to them by members working on that unit, such as an increase in violence, back injuries, needlestick injuries, a lack of protocols for the handling and administration of cytotoxic drugs, inadequate ventilation, lack of training, etc.

- For example, when staff concerns such as needlestick injuries are brought to the inspecting worker’s attention, they should record details, including the unit where the needlestick injury occurred, the procedure being performed, patient interference with the procedure, the type of sharps device being used, This information should then be taken back to the JHSC to analyze, with the intention of making a recommendation for the removal of unsafe sharps devices by replacing them with safety-engineered sharps devices.

- A block diagram of the different areas to be inspected will facilitate the identification of a hazard, where it is present and who is exposed or likely to be The block diagram is a floor plan of a work area, such as a nursing unit. It shows location of all equipment, chemicals, drugs, isolation rooms, storage areas, doors, windows and the location of workers.

- Inspection software is available and several large facilities use handy pre-programmed tablets with information including identification of the area, previous inspection reports,

- The inspecting worker should list the substances, physical hazards and processes present or utilized in each work They can ask the workers in the area if they are aware of any hazards to their health and safety or to their co-workers’ health and safety. They should also ask workers if they reported these hazards to their supervisor. If so, what action was taken if any? They may need to work hard to elicit information about hazards and concerns. It has been ONA’s experience that too often health care workers believe that hazards are just part of the job and, as such, may not recognize or report problems that can in fact be reduced or eliminated, and that workers must by law report. The inspection is a perfect opportunity not only to obtain information from workers, but also to educate them about their legal duties to report hazards, faulty equipment, etc.

- The worker can also monitor employer programs and ensure that workers have received appropriate Where training was provided, check that workers have retained their knowledge/skills (e.g., workers who have been fit tested for a respirator should be able to confidently confirm that they remember how to put it on and take it off, indicate which respirator they were fitted for and when one should be used).

- The WHMIS program ensures that products are adequately labeled, providing information regarding their The employer must supply this information by providing Safety Data Sheets (SDS). The SDS, which is obtained from the supplier or manufacturer of the product, provides advice on the short-term or acute effects of exposure to the product but may not provide information about long-term or chronic effects. It is important for the inspecting worker to know that additional information may be obtained from sources, such as the Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety (CCOHS), the WHSC, the PSHSA and ONA.

- The inspecting worker should review protocol or procedure book recommendations, if any, to determine whether current procedures adequately protect workers carrying out a process or procedure (e.g., appropriate infection control measures).

- More and more of our members require accommodation of their disabilities in the Return to Work or modified work plans are negotiated by workplace parties. During workplace inspections, the inspecting worker should review the work of accommodated members to ensure they are working safely within their restrictions and that proper equipment, and all accommodation arrangements are available.

- Also, during the inspection, or at any other time when an accommodated worker raises a health and safety concern, the JHSC and Bargaining Unit representative should work to ensure the worker’s ongoing In some cases, an injured or ill worker may stop working because of pain from the work or because they believe the work will further harm them. Union leaders and JHSC members should be alert to such situations, which may actually constitute work refusals under the Act (for more information about handling concerns of our working injured and ill members, see Appendix F, Safe Return to Work Algorithm, and ONA booklet, My Right To Refuse Unsafe Work: A Guide for ONA Members).

- In our experience, when accommodating workers, employers rarely consider applying a lift program, which includes training and the purchase of ergonomic equipment, and more often than not, they simply attempt to accommodate workers with graduated hours or a buddy system. This may be suitable for some truly temporary accommodations, but in permanent arrangements, ergonomic equipment must be If the worker is having difficulties, an inspecting worker can report this to the committee, which may identify the lack of a safe lift program, training and equipment, such as mechanical lifts and ergonomic supplies that could adequately accommodate the worker (consider revising the sample Lifting Recommendation at Appendix B).

- Following any inspection/investigation, the inspecting worker should report identified hazards to a supervisor and then meet with other worker members of the JHSC to review the inspection/investigation Health and safety hazards noted in the inspection should be discussed, possible solutions to unresolved issues developed and written recommendations drafted (for sample recommendations, see Appendix B). The inspecting worker should then take the report and recommendations to the next full committee meeting, and the full committee should consider possible solutions and make written recommendations to the employer. Following failure of good faith attempts to reach consensus, the worker co-chair can submit written recommendations to the employer independently, to which the employer is obligated to reply in writing within 21 days.

Role of ONA Health and Safety Member on the JHSC

The health and safety member on the JHSC:

- Is elected/selected by the

- Has a working knowledge of the Occupational Health and Safety Act, regulations and available If the JHSC member feels they need more information and/or resource materials, they should contact their Bargaining Unit President and/or LRO for support.

- Responds to the health and safety concerns of members and all workers seeking

- Attends all JHSC meetings and worker caucus preparation

- Takes unresolved health and safety concerns to the JHSC for resolution and advocates for recommendations in writing that will resolve A sample recommendation can be found in Appendix B, or for more sample recommendations, log onto the members’ section of the ONA website at www.ona.org and follow the links to the health and safety section.

- Reports back and maintains close contact with the Bargaining Unit Leadership team regarding health and safety

- May act as co-chairperson of the

- Ensures that JHSC meeting agenda items are submitted in time for discussion at the

- Participates in workplace inspections, as required, and identifies hazards to supervisors and the committee to engage it in finding solutions to eliminate those

- May participate in the development and distribution of JHSC’s meeting

- May record and distribute JHSC meeting

- Liaises with the Bargaining Unit’s negotiating committee regarding improvements to the collective agreement in the areas of occupational health and safety and workers’ compensation.

- Liaises with the health and safety representatives of other local unions in the

- Caucuses with other health and safety committee members from other unions before meetings to gain consensus on approaches to

- May contact the MLTSD if the IRS fails and health and safety concerns remain

- Has completed at least a basic occupational health and safety course (strongly recommended).

- Assists in carrying out the mandate of the

- Acts as the certified worker when selected by worker members of the

- May network with other JHSC members in other ONA

Administrative Process of the JHSC

- The JHSC should develop “Terms of Reference” (a template can be found on the ONA website at ona.org under health and safety) that augments the Act and sets out rules governing the work of the committee. Terms of Reference are not required by the Act, but are a good idea, need to be mutually agreed to with the employer, and should be reviewed annually. Be cautious of developing Terms of Reference that end up delaying the resolution of health and safety concerns through quorum issues.

- The committee should reinforce the cooperative solving of health and safety problems and facilitate information dissemination among workers and

- Any worker may raise a concern verbally or in writing regarding health and safety in the workplace. If possible, health and safety issues should be addressed to the worker’s immediate supervisor before they are brought to the

- Unresolved health and safety concerns should be brought to the JHSC for discussion and resolution. Unresolved concerns should be raised as high as necessary as quickly as necessary to protect

- In the Terms of Reference, the committee can establish the quorum necessary to conduct business and indicate that all issues should be resolved by consensus, not by

- The chairpersons should agree on an agenda and forward a copy to all committee members at least five working days prior to the A provision should be made to allow additions to the agenda with shorter notice or additional emergency meetings where pressing circumstances exist. This procedure should be set out in any Terms of Reference.

- One JHSC member should be designated to record minutes of proceedings at all committee meetings. In some facilities, the employer may provide a secretary to perform this

- ONA JHSC members should ensure that all problems, resolutions, timeframes and responsibility for action are accurately recorded in the

- In the event of disagreement over an individual agenda item, the differing positions should be recorded in the

- Minutes should be signed by both co-chairs or their alternates, who are responsible for ensuring the signed minutes are posted, circulated to all committee members and senior management, and filed at the

- Minutes should be

- All recommendations of the JHSC or either co-chair should be forwarded in writing to the employer for a response in writing within 21 days (Section 9 (20)). Usually this is the CEO or Health Administrator and should not be confused with the employer members sitting on the JHSC, the occupational health and safety department, or

- Efforts should be made to promote cooperation among representatives from all unions representing workers on the (See Appendix D for a joint union memo affirming health- care union commitment to work together in health and safety.)

Role of the MLTSD in Occupational Health and Safety at the Workplace

The Occupational Health and Safety Act is administered by the MLTSD’s Occupational Health and Safety branch, and health care facilities are usually inspected by regional safety inspectors who may be aided by health care inspectors from the branch’s Health Care Unit. See contact information at Appendix G Resources.

Inspector’s Powers

Under Section 54, an inspector has the authority to:

- Enter any workplace without a warrant or

- Question any person, either privately or in the presence of someone else, who may be connected to an inspection, examination or

- Handle, use or test any equipment, machinery, material or agent in the workplace and take away

- Examine documents or records and remove them from the workplace to make copies; this also includes the taking of

- Require that any part of a workplace or the entire workplace not be disturbed for a reasonable period of time to conduct an examination, inspection or

- Require that any equipment, machinery or process be operated or set in motion or that a system or procedure be carried out that may be relevant to an examination, inquiry or

- Examine and copy material concerning workers’ training

- Direct a JHSC member representing workers, or a health and safety representative, to inspect the workplace at specified

- Seize articles permitted by a

- Require the employer, at its expense, to have an expert test and provide a report on equipment, machinery, materials, agents, etc. This also includes having a professional engineer test equipment or machinery and verify it is not likely to endanger a worker or to stop use pending such test

- Require an employer to provide information about any process or agent used in the workplace, or intended to be used there, and the manner of its use, which includes information on ingredients, composition and properties of the agent, toxicological effects of the agent, effects when exposed to skin, inhaled or ingested, and the protective and emergency measures that would be used in the event of

In addition, an inspector may order an employer to conduct, at the employer’s expense, an investigation of a complaint of workplace harassment (Sections 32.0.7, 55.3).

An employer must afford a worker member of the JHSC, selected by the workers, an opportunity to accompany an inspector on an inspection (Section 54 (3)). In smaller workplaces, the health and safety representative must be given the opportunity. If neither is available, the union(s) must be given an opportunity to select someone, and where there is no union, workers must be permitted to select someone. The worker must be considered at work during the inspection and paid at the applicable rate of pay.

In the event that no such worker is available for the inspection, the inspector must endeavor to consult with a reasonable number of workers about their health and safety concerns.

An inspector can also be called in to investigate a complaint. Remember, given that our members’ right to refuse unsafe work is likely limited, the only thing standing between them and imminent jeopardy may be a call to the MLTSD. Because our members have a limited right to refuse unsafe work, the MLTSD has committed to responding to our members’ complaints on a “priority complaint basis” (see confirming memo at Appendix E).

Inspector’s Orders

Where violations have occurred, the inspector may issue written orders to the employer to comply with the law within a certain period of time or, if the hazard is imminent, to comply immediately. An inspector’s order may require the employer to submit a plan to the Ministry, specifying when it will be complying with the order (Section 57).

An inspector may direct a designated JHSC worker member to inspect all or parts of the workplace at specified intervals (Section 55).

An order may also be issued to an employer – with five or fewer workers – to write and post workplace violence and harassment policies (Section 55.1).

In addition, an inspector may order an employer to engage, at the employer’s expense, a third- party to investigate a claim of sexual harassment (Section 55.3).

When an order has been made to correct a violation of the Act or regulations and the violation in question is dangerous to the health or safety of a worker, the inspector may also order the following:

- Any place, equipment or machinery, material process, not be used until the violation has been corrected.

- The work be

- The workplace be cleared of workers, and access to the workplace be prevented until the hazard is

- Any hazardous chemical, physical or biological agent not be